Payment Complexity Demands Data Integrity

- By Bonnie Kirschenbaum, MS, FASHP, FCSHP

ONE OF THE principles of highly reliable organizations is a sensitivity to operations.1 Without a doubt, this can be applied to the very complex nature of healthcare payment with its myriad of workflows, ever-changing rules, processes and the overlay of technology that can, and often does, lead to workarounds. Staff simply finds a way of avoiding what they see as inefficiencies, annoyances or unwelcome changes, particularly if they don’t agree with them.

But, expectations abound when new administrations bring new ideas and policy changes! Just days after the transfer of power, the new Department of Government Efficiency team has focused on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Considering that the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) controls hundreds of billions of dollars in annual payments to healthcare providers, it’s inevitable that any search for fraud, waste or abuse of spend would target agencies such as Medicare and Medicaid. The Government Accountability Office (GAO), a nonpartisan watchdog, has concluded that Medicare and Medicaid represent more than 40 percent of improper payments across the federal government.2

“Both Medicare and Medicaid are susceptible to payment errors — over $100 billion worth in 2023,” GAO wrote in April 2024.3 They define improper payments as any payments that should not have been made or that were made in an incorrect amount, including overpayments and underpayments. Modern Healthcare reports that “Improper payments made through programs of [HHS], which ballooned during the COVID-19 pandemic, are on the decline but still amounted to more than five percent of outlays by the agency last year — or about $88.5 billion.” Improper payments in Medicaid and Medicare Advantage have decreased since 2021, but problem payments in Medicare fee-for-service have increased, and improper payments in the Medicare prescription drug benefit program have seen a small increase since 2022.4

These billions of dollars in payments are the sum total of every transaction that all providers, pharmacies, healthcare facilities and organizations have submitted for payment. As such, following are things healthcare organizations should consider.

An Updated Drug Database

A living, active database of all medications, biologicals and products should be created that will be used in claims. Included should be the drug’s name, strength, dosage, national drug code (NDC), healthcare common procedure coding system (HCPCS) code, billing unit and sell price. This data set is known as the charge description master (CDM) that should be linked to the drug dictionary or pharmacy drug master that populates the electronic health record so computerized provider order entries automatically create the charge posted on the claim. The CDM should be kept current by adding new items and deleting obsolete ones.

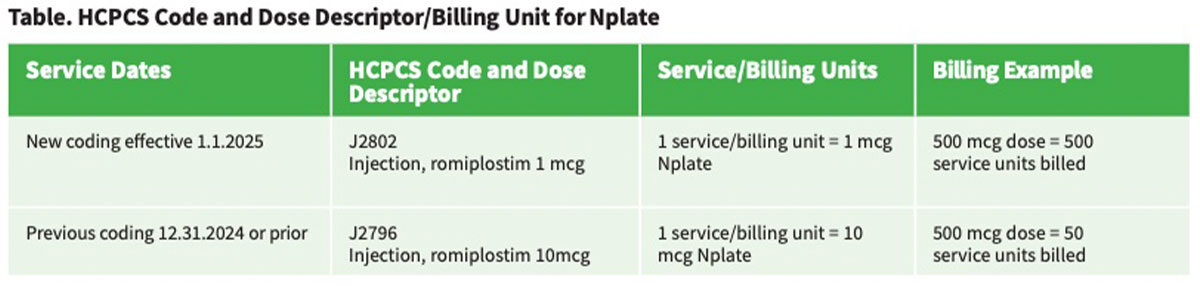

The NDC code is critical: The first set of numbers identifies the manufacturer, and the remaining numbers identify the drug and strength. It is essential to ensure that the manufacturer identified by the NDC code matches the product being purchased. Codes and billing units may change, as in the example provided in the table. Note that both the HCPCS code changes and the billing/service unit changes. Failure to update the CDM results in losing 90 percent of the revenue for the product! Therefore, these errors should be identified and eliminated:

1) Outdated CDMs. Update CDMs when the manufacturer and the product’s NDC change. Keep the CDM in sync with what is being purchased.

2) Use of miscellaneous HCPCS codes rather than the drug-specific ones. Miscellaneous HCPCS codes should be reserved only for the very brief time that a drug is used before a HCPCS code has been assigned; it always must be accompanied by the NDC code.

3) Reusing CDM numbers for new products rather than creating new ones. Always create a new CDM for a new product.

Billing for Waste/Discarded Drug

CMS requires compliance with policies for drug waste billing. Therefore, organizations must ensure wasted product was actually wasted and not used in any other manner. CMS bills the manufacturer for the amount submitted in waste billing. Inaccurate descriptions and NDC numbers are subject to audit.

The 340B Program

The growth of the 340B program has outpaced its original provisions and often lacks transparency. Organizations should focus on potential areas of change. Several states have added legislation regulating use of the 340B program. It remains to be seen as to whether or not states can modify a federal program.

Facility Fees

Facility fees are intended to cover costs of maintaining medical facilities, including hospitals, physician offices and clinics, but costs often surprise patients because information is not transparent. The pending Primary Care and Health Workforce Act (S. 2840) is seeking to broadly restrict facility fees by blocking hospitals from charging health plans facility fees for many evaluation, management and telehealth services.

Site-Neutral Policies

Site-neutral payment refers to uniform care reimbursement regardless of care setting. Hospitals are actively opposed to this method, as it would lower their pay. It remains to be seen whether a site-neutral Medicare provision will be included in subsequent major healthcare packages that the Senate Finance Committee propose. However, commercial payers often mandate site of care, so organizations must ensure they know the payer for each patient and what the payers’ stipulations are.

Claims Denials

Payers hold the keys to payments, and unfortunately, claim denials are rampant. Payers must appropriately plan and manage benefit coverage for highinvestment drugs being used, as well as those in the pipeline. Their tools and tactics include prior authorization, bundled payments, attempting to move drug products from the medical into the pharmacy benefit, mandating treatment pathways or closed formularies, stipulating site of care and even creating risk-sharing collaborations.

It’s important to incorporate a facility’s agreed-upon payer contract terms into practice and policies. Denials prevention is more efficient than denials management, which often is the fruitless, time-and-resource-consuming quest to overturn denials and collect revenue. Prevention hinges on telling the patient’s story completely and accurately with appropriate, codable documentation, including the medical necessity of the service and treatment.

References

- Sexton, JB, Thomas, EJ, Helmreich, RL, et al. High Reliability Organizations: A Framework for Improving Patient Safety in Healthcare. Patient Safety and Quality, 2014;18(1):1-10.

- Wilde Mathews, A, and Essley Whyte, L. DOGE Aides Search Medicare Agency Payment Systems for Fraud. The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 5, 2025. Accessed at www.wsj.com/politics/elon-musk-doge-medicare-medicaid-fraud-e697b162.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Medicare and Medicaid: Additional Actions Needed to Enhance Program Integrity and Save Billions, April 16, 2024. Accessed at www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-107487.

- Broderick, T. HHS, CMS Improper Payments: $88.5B in 2024. Modern Healthcare, Feb. 7, 2025. Accessed at www.modernhealthcare.com/politics-policy/hhs-cms-improper-payments-2024.