Myths & Facts: Prenatal Care

With almost a quarter of women receiving inadequate prenatal care in the U.S., more needs to be done to inform women about the myths surrounding this essential healthcare service.

- By Ronale Tucker Rhodes, MS

A healthy pregnancy is one of the best ways to promote a healthy birth. But, the chances of a healthy pregnancy are dependent upon getting early and regular prenatal care, which can begin even before pregnancy with a pre-pregnancy care visit to a healthcare provider and extend through birth, as well as following prenatal healthcare guidelines.

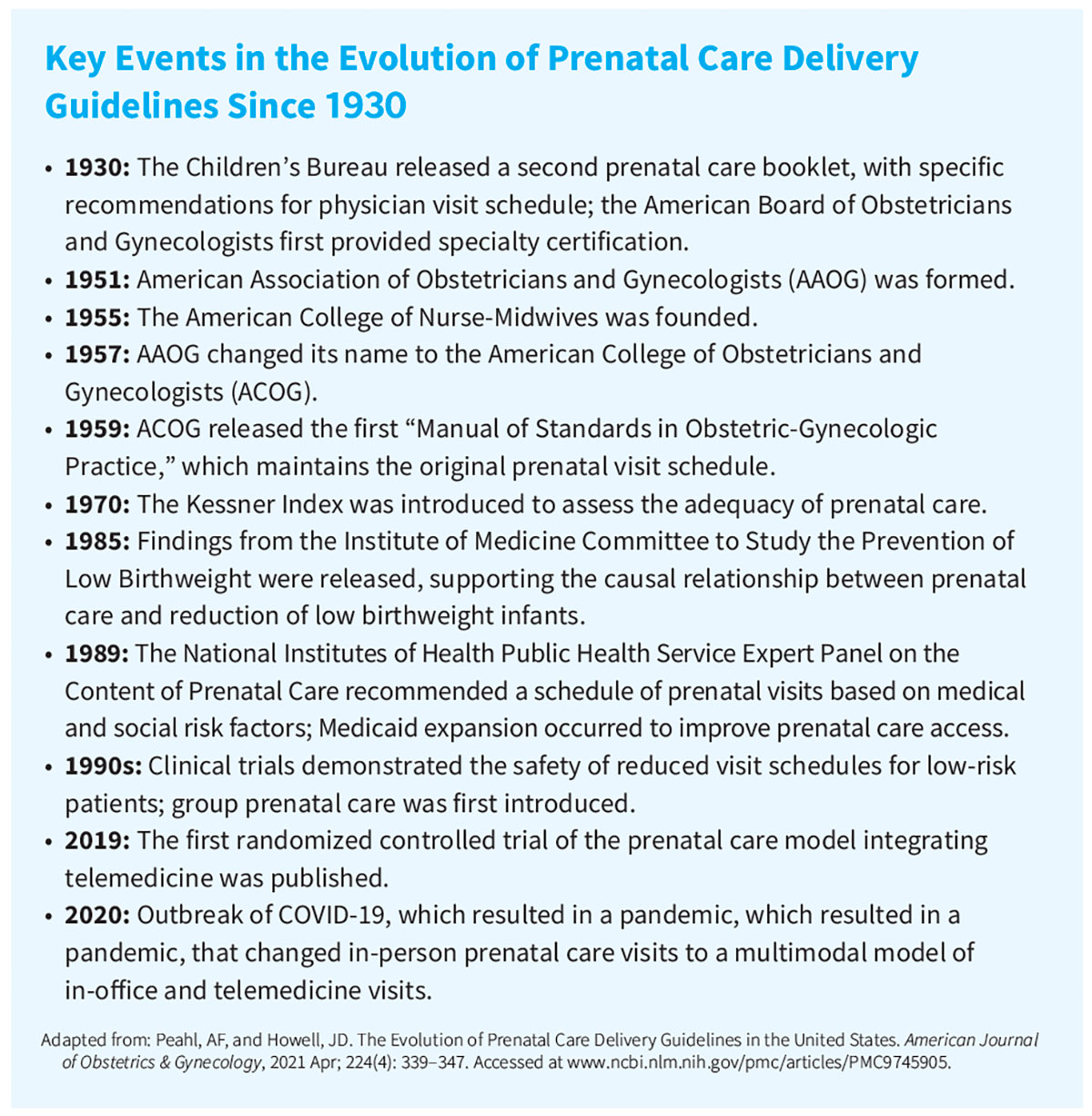

The recommendations for prenatal care doctor visits date back to the 19th century when new data revealed high rates of infant and maternal mortalities. These discoveries culminated in the first codification of a prenatal visit schedule in 1930 by the Children’s Bureau, which recommended 12 to 14 prenatal visits during pregnancy. It was hoped the Bureau’s schedule could prevent harm to mothers and babies. And, until the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) was founded, resulting in technological advancements in laboratory testing and ultrasonography, as well as calls from the National Institutes of Health Task Force for changes in prenatal care delivery in 1989, prenatal care recommendations continued to be the same as they had been since 1930: monthly visits until 28 weeks’ gestation, bimonthly visits until 36 weeks’ gestation and weekly visits until delivery.1 Since then, that schedule remained essentially unchanged for almost a century until the pandemic in 2020 that changed in-person prenatal care visits to a multimodal model of in-office and telemedicine visits.2

In 2022, there were 3,667,758 births in the United States, or a birth rate of 11.0 per 1,000 population (the latest available data as of this writing).3 Also in 2022, 77 percent of live births in the United States were to women receiving early prenatal care, 16.3 percent were to women beginning care in the second trimester and 6.8 percent were to women receiving late or no prenatal care. Inadequate prenatal care is pregnancy-related care beginning in the fifth month of pregnancy or later or less than 50 percent of the appropriate number of visits for an infant’s gestational age. In 2022, about one in seven infants (15.5 percent of live births) was born to a woman receiving inadequate prenatal care in the United States,4 which can lead to premature pregnancy, intrauterine growth retardation, low weight at birth, and maternal and child mortality as a result of infections in the perinatal and postnatal periods.5

What’s more, in addition to inadequate prenatal care among almost a quarter of pregnant women in the United States, the many myths surrounding healthcare recommendations such as alcohol consumption, exercise, nutrition and more result in other pregnancy complications. As such, during prenatal visits, physicians should encourage regular checkups and help to dispel the many myths surrounding pregnancy to ensure their patients have healthy pregnancies.

Separating Myth from Fact

Myth: Prenatal care starts after a positive pregnancy test.

Fact: Women should schedule their first prenatal appointment as soon as they find out they are pregnant, but women can benefit from prepregnancy care, too. According to ACOG, a prepregnancy care checkup can find things that could affect a woman’s pregnancy, which is important because the first eight weeks of pregnancy is the time when major organs develop in a fetus. During the prepregnancy visit, the OB-GYN will discuss diet and lifestyle, medical and family history, medications and past pregnancies. He or she will also review vaccination history to be sure all vaccines recommended for a women’s age group have been received. In addition, sexually transmitted infections and how to protect against them will be discussed.6

Myth: Women over age 35 are at high risk for pregnancy.

Fact: The truth is that most women 35 or older have a normal pregnancy and healthy baby. Plus, there are some advantages to being an older mom, including financial stability and having more life experience that can help during the parenting journey. Nevertheless, women should talk to their OB-GYN about the types of complications that can occur from underlying health issues that arise more often with age, including diabetes and high blood pressure. Getting proper treatment for these issues can better women’s chances of having a healthy pregnancy.7 That said, while the risks are low, there is a higher risk of pregnancy-related complications that might lead to a C-section delivery. The risk of chromosomal conditions is higher, and babies born to older mothers have a higher risk of certain chromosomal conditions such as Down syndrome. In addition, the risk of pregnancy loss is higher.8

Myth: All bleeding during the first trimester means a miscarriage.

Fact: Women who experience bleeding during any stage of pregnancy should talk to their OB-GYN to assess what’s going on. This is because vaginal bleeding during pregnancy has many causes, some of which are serious and others that are not. In fact, bleeding can occur early or later in pregnancy.9 However, bleeding, even during the first trimester, is not always associated with a miscarriage. Vaginal bleeding is extremely common in the first trimester, occurring in 20 percent to 40 percent of women.7

According to ACOG, “Light bleeding or spotting can occur one to two weeks after fertilization when the fertilized egg implants in the lining of the uterus. [And], the cervix may bleed more easily during pregnancy because more blood vessels are developing in this area.”9

Myth: It’s OK for women to eat as much as they want while pregnant.

Fact: Eating for two is a cute adage often used during pregnancy, but eating twice as much can put women at increased risk of pregnancy complications. According to a 2015 government report, 47 percent of American moms gain too much weight during pregnancy.10

Many women find it difficult to figure out the right balance of food intake. Most physicians recommend eating an extra 200 to 400 calories a day in the second trimester and about 500 calories a day more in the third trimester, but that may vary for women who are overweight or underweight. Of course, those expecting twins or triplets will need to eat more.10

Medline calorie guidelines for most normal-weight pregnant women are about 1,800 calories per day during the first trimester, about 2,200 calories per day during the second trimester and about 2,400 calories per day during the third trimester. Medline’s general guidelines for healthy weight gain are:11

• Normal total weight gain for a healthy woman is 25 to 35 pounds (11 to 16 kilograms) during pregnancy.

• Overweight women should gain only 10 to 20 pounds (4 to 9 kilograms) during pregnancy.

• Underweight women should gain more (28 to 40 pounds or 13 to 18 kilograms) during pregnancy.

• Women with multiples (twins or more) should gain 37 to 54 pounds (16.5 to 24.5 kilograms) during pregnancy.

Myth: It’s OK for women to have an occasional glass of wine during pregnancy.

Fact: This topic is actually debated today. For years, women have been told to abstain completely from alcohol during pregnancy. But, more recently, many women are being told by their OB-GYNs that on an individual basis, the occasional glass of wine would unlikely harm the baby due to the limited amount of alcohol being introducing into the body.12

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “There is no safe time for alcohol use during pregnancy.” And that includes all types of alcohol, including red or white wine, beer and liquor since it “is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, preterm birth, stillbirth and sudden infant death syndrome. Alcohol use during pregnancy can cause a range of lifelong behavioral, intellectual and physical disabilities known as fetal alcohol spectrum (FAS) disorders.”13

But, says the American Pregnancy Association, while it is known that excessive drinking is the cause of many of the complications that can occur during pregnancy as a result of alcohol, these risks may not be associated as strongly with occasional drinking. FAS occurs when the pregnant mother drinks excessive amounts of alcohol. Unfortunately, there is no specific amount that has been determined to cause FAS, which is why the safest answer to whether or not a woman should drink during pregnancy is that it should be avoided, if at all possible.12

Myth: Pregnant women shouldn’t fly/travel by air.

Fact: According to ACOG, “In most cases, pregnant women can travel safely until close to their due dates.” During a healthy pregnancy, occasional air travel is almost always safe, and most airlines allow women to fly domestically until about 36 weeks of pregnancy. However, pregnant women should avoid flying if they have a medical or pregnancy condition that may be made worse by flying or could require emergency medical care (most common pregnancy emergencies usually happen in the first and third trimesters).

That said, research shows that any type of travel lasting four hours or more — whether by car, train, bus or plane — doubles the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and being pregnant is an extra risk factor for DVT. But this risk can be mitigated by drinking lots of fluids without caffeine, wearing loose-fitting clothing, walking and stretching at regular intervals, and wearing special stockings that compress the legs, either below the knee or full length, to help prevent blood clots from forming.14

Myth: Pregnant women shouldn’t exercise.

Fact: Exercise is important during pregnancy for weight control, stress management and overall health. According to ACOG, women should try performing 150 minutes of moderate physical activity each week, along with muscle-strengthening activities on two days or more a week. The number of minutes can be divided into shorter workout sessions throughout the week, for example, performing a 30-minute workout five days per week.15

According to an expert review of current literature published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, “Conclusive data from both validated activity questionnaires and accelerometers indicate that physical activity is safe during pregnancy. In addition, studies of physical activity during pregnancy that evaluate pregnancy outcomes have found reduced risks of preterm birth, preeclampsia and gestational diabetes and improved mental health among individuals who regularly engage in physical activity.” According to the experts, “Providers should encourage physical activity before and during pregnancy and educate patients regarding the benefits and safety of physical activity.”16

Myth: Sex during pregnancy can be harmful for the baby.

Fact: In most cases, sex during pregnancy poses no risk to the mother or baby. Many studies have concluded that vaginal sex during pregnancy has no increased risk of preterm labor or premature birth. However, if a doctor considers someone to be at high risk, he or she may recommend that the woman avoids sexual intercourse during the pregnancy or just in the later stages.17

Myth: Pregnant women should not take over-the-counter (OTC) and/or prescription medicines or supplements.

Fact: A common concern about prenatal care involves the use of OTC medications. Unfortunately, high-quality research on the safety and effectiveness of OTC medications in pregnancy is limited. In fact, “fewer than 10 percent of medicines approved since 1980 have enough information to determine their safety during pregnancy. This is because pregnant people are often not included in studies that determine the safety of new medicines. As a result, pregnant people and healthcare professionals have limited information to make informed treatment decisions during pregnancy.”18

Nevertheless, medicine use during pregnancy is common. “About nine in 10 women report taking some type of medicine during pregnancy. About seven in 10 report taking at least one prescription medicine.”18 According to studies, in the first trimester, the most common OTC medications taken are ibuprofen, acetaminophen, aspirin, naproxen, pseudoephedrine and docusate.19

Therefore, CDC recommends pregnant women discuss all medicines they take, including prescriptions, OTC medicines, herbal and dietary supplements and vitamins with their healthcare providers.18

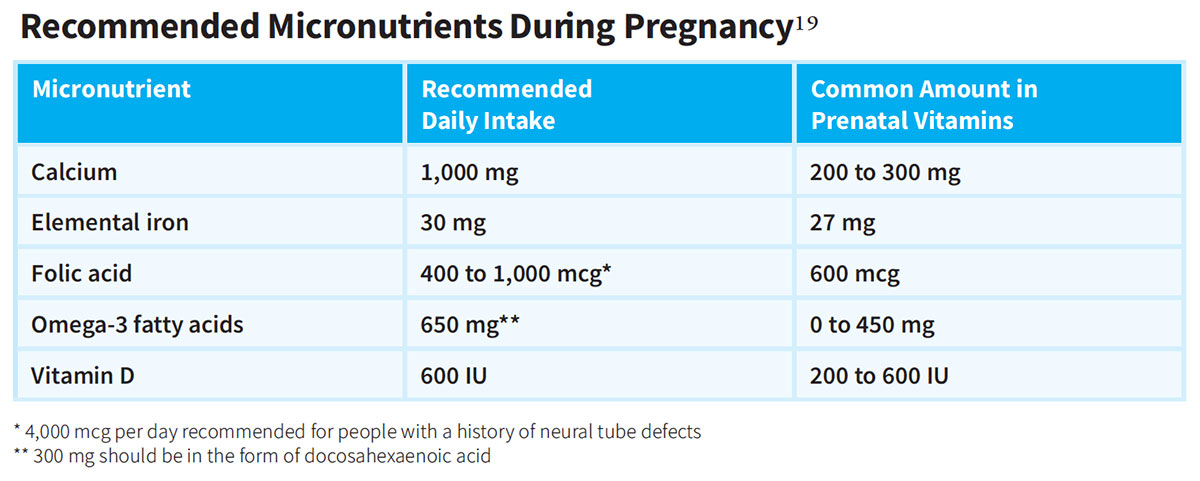

According to the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), “A well-balanced diet rich in vitamin D, folic acid, iron, calcium, omega-3 fatty acids and other micronutrients should be encouraged for pregnant patients. Prenatal vitamins are recommended because they provide folic acid, iron, calcium and vitamin D. Ideally, they should be started before conception and should contain at least 400 mcg of folic acid, 30 mg of elemental iron, 200 to 300 mg of calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D.”19 (See table for recommended micronutrients.) Prenatal vitamins can be obtained OTC or by prescription. Some examples of prescription prenatal vitamins include VitaMedMD One RX, VitaPearl and VitaTrue.

Myth: It’s dangerous if a pregnant woman is past her due date.

Fact: It’s normal for women to give birth before or after their set due date. The due date is merely a calculated estimate of when the baby has been developing in the womb for 40 weeks. A pregnancy that goes beyond the 40 week mark and lasts between 41 or 42 weeks is called “late term.” A pregnancy that lasts longer than 42 weeks is called “postterm.”

Women most likely to have a postterm pregnancy are those who are in their first pregnancy, if the baby is a boy, if the woman’s body mass index is 30 or higher (obese), if the woman has had a prior postterm pregnancy, or if the due date was calculated wrong due to confusion about the last menstrual period. An OB-GYN will closely watch the baby’s size, heart, weight and position if a woman goes past her due date. If necessary, the OB-GYN will recommend a labor induction to help promote a vaginal birth if the health of the mother or fetus is at stake.7,20

Most women who give birth after their due dates have uncomplicated labor and give birth to healthy babies. Risks associated with postterm pregnancy include stillbirth, macrosomia, postmaturity syndrome, meconium in the lungs of the fetus (which can cause serious breathing problems after birth) and decreased amniotic fluid (which can cause the umbilical cord to pinch and restrict the flow of oxygen to the fetus). However, problems occur in only a small number of postterm pregnancies.20

Myth: Women who opt for telehealth visits vs. in-person office visits receive inadequate prenatal care.

Fact: Postpandemic, it is now known that in-person prenatal visits are not all necessarily superior to telehealth visits. This came to light in the 2023 study mentioned previously that examined the multimodal model of in-office and telemedicine visits. In the cohort study of 151,464 pregnant individuals, after implementation of a multimodal prenatal healthcare model with telemedicine and in-office visits during the pandemic, there were no changes in rates of preeclampsia and eclampsia, severe maternal morbidity, cesarean delivery and preterm birth compared with the prepandemic rates; however, there was an increase in the rate of neonatal intensive care unit admissions during the second pandemic period. These findings suggest that a multimodal prenatal healthcare model combining in-office and telemedicine visits performed adequately compared with in-office only prenatal healthcare, supporting its continued use after the pandemic.2

Dispelling the Myths Now

It may seem a bit unbelievable, and no doubt disturbing, but women in the United States are more likely to die from childbirth than women living in other developed countries. Therefore, Healthy People 2030 is focusing on preventing pregnancy complications and maternal deaths and helping women stay healthy before, during and after pregnancy.21 One of the goals of Healthy People 2030 is to increase the proportion of pregnant women who receive early and adequate prenatal care to 80.5 percent of the population (vs. 77 percent currently).4 According to Healthy People 2030, women who receive recommended healthcare services before they get pregnant are more likely to be healthy during pregnancy and to have healthy babies. And, strategies to help pregnant women get medical care and avoid risky behaviors — such as smoking or drinking alcohol — can also improve health outcomes for infants.21

Unfortunately, whether the Healthy People 2030 initiative becomes reality seems in jeopardy. A report released by CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics in August showed that the number of women going through pregnancy without prenatal care is growing — even though the overall number of babies born in the U.S. is falling. In fact, an analysis of birth certificates revealed “the percentage of mothers without any prenatal care rose from 2.2 percent in 2022 to 2.3 percent in 2023.” According to the authors of the report, the lopsided trend may reflect, in part, a growing number of women unable to access OB-GYN care after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022. “In many counties, you can’t even find a prenatal care provider,” said Brenna Hughes, MD, MSc, executive vice chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University in Durham, N.C. “If you have limited resources and have to travel to be able to access prenatal care, it is going to be a deterrent.”22

Therefore, now more than ever, timely intervention, including dispelling the many myths concerning prenatal care, from doctors can significantly cure or prevent problems, improving outcomes for unborn babies and mothers.

References

1. Peahl, AF, and Howell, JD. The Evolution of Prenatal Care Delivery Guidelines in the United States. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2021 Apr; 224(4):339–347. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9745905.

2. Ferrara, A, Greenberg, M, Zhu, Y, et al. Prenatal Health Care Outcomes Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Pregnant Individuals and Their Newborns in an Integrated U.S. Health System. JAMA Network Open, 2023;6(7):e2324011. Accessed at jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2807379.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. Births and Natality. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm.

4. March of Dimes. Prenatal Care. Accessed at www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/data?reg=99&top=5&stop=34&lev=1&slev=4&obj=1.

5. Quadrado da Rosa, C, Silva da Silveira, D, and Soares Dias da Costa, J. Factors Associated with Lack of Prenatal Care in a Large Municipality. Revista de Saúde Pública, 2014 Oct; 48(6): 977–984. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4285828.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Good Health Before Pregnancy: Prepregnancy Care. Accessed at www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/good-health-before-pregnancy-prepregnancy-care.

7. Moreland OB-GYN. 11 Pregnancy Myths and Facts Every Woman Needs to Read. Accessed at www.morelandobgyn.com/blog/pregnancy-myths.

8. Mayo Clinic. Getting Pregnant. Accessed at www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/getting-pregnant/in-depth/pregnancy/art-20045756.

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Bleeding During Pregnancy. Accessed at www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/bleeding-during-pregnancy.

10. Montoya, M. Are Pregnant Women Really Eating for Two? Not Quite. University of New Mexico Health, Jan. 14, 2021. Accessed at unmhealth.org/stories/2021/01/eating-for-two.html.

11. Medline. Eating Right During Pregnancy. Accessed at medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000584.htm.

12. American Pregnancy Association. Can You Drink Wine While Pregnant? Accessed at americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/is-it-safe/wine-during-pregnancy.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and Pregnancy. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/alcohol-pregnancy/about/index.html.

13. LeWine, HE. Drinking a Little Alcohol Early in Pregnancy May Be Okay. Harvard Health Publishing, Jan. 29, 2020. Accessed at www.health.harvard.edu/blog/study-no-connection-between-drinking-alcohol-early-in-pregnancy-and-birth-problems-201309106667.

14. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Travel During Pregnancy Frequently Asked Questions. Accessed at www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/travel-during-pregnancy.

15. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Good Health Before Pregnancy: Prepregnancy Care. Accessed at www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/good-health-before-pregnancy-prepregnancy-care.

16. Gascoigne, EL, Webster, CM, Honart, AW, et al. Physical Activity and Pregnancy Outcomes: An Expert Review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology MFM, 2023 Jan; 5(1): 100758. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9772147.

17. Medical News Today. What To Know About Sex During Pregnancy. Accessed at www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321648.

18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Medicine and Pregnancy: An Overview. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/medicine-and-pregnancy/about/index.html.

19. Caro, R, and Fast, J. Pregnancy Myths and Practical Tips. American Family Physician, 2020;102(7):420-426. Accessed at www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2020/1001/p420.html.

20. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. When Pregnancy Goes Past Your Due Date. Accessed at www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/when-pregnancy-goes-past-your-due-date.

21. Healthy People 2030. Pregnancy and Childbirth. Accessed at health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/pregnancy-and-childbirth.

22. Edwards, E. Births in the U.S. Declined Again and More Pregnant Women Are Going Without Prenatal Care, a CDC Report Finds. NBC News, Aug. 20, 2024. Accessed at www.yahoo.com/news/births-u-declined-again-more-060100350.html.