Myths and Facts: Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Better understanding of this debilitating and painful condition stemming from a previous trauma is needed to demystify it and dispel the mistaken notion that the suffering is all in one’s head.

- By Ronale Tucker Rhodes, MS

SAMANTHA REEB WAS an active college freshman and just beginning her adult life when it “changed in the blink of an eye.” The van that she and seven of her high school friends were riding in was rear-ended by a driver traveling 60 mph. Regrettably, none of the teens was wearing a seatbelt, and all were badly injured. Samantha’s legs were badly injured and, afterward, she was in excruciating and unrelenting pain that left her unable to walk. But, doctors couldn’t tell her why, and her first doctor even claimed she was simply making it up. Until, finally, she was diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). After numerous medications and spinal injections, none of which worked, she was referred to a pain clinic, where she learned to manage her pain and walk again. “Even though I was stuck with this horrible pain for the rest of my life, I put in so much hard work, and I finally got something back,” explains Samantha. “At that point, I realized something: I could either live the rest of my life feeling sorry for myself, or I could live the rest of my life. So that is what I chose to do.”1

CRPS is a progressive disease of the sympathetic nervous system. Those affected by CRPS have pain characterized as constant, extremely intense and out of proportion to the original injury. It is ranked by the McGill Pain Index as the most painful form of chronic pain that exists today.2 “Most people wouldn’t last 10 minutes in the shoes of someone who feels the pain we do,” says Samantha. “We live every day with more pain than a cancer patient or a woman in labor or someone getting an amputation.”

There are two types of CRPS. CRPS type I, previously known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), involves injuries to the soft tissue of the affected area. Soft tissue injuries can include sprains, burns, tears and strains, and they can occur due to inflammation of body parts such as arthritis, bursitis and tendonitis. CRPS type II, previously known as causalgia, involves damage to at least one major nerve that has been clearly defined, and its cause may or may not be known.3

While CRPS can occur in anyone, it is more common in women, and it can occur at any age, most commonly in individuals aged 40 years to 60 years. It is very rare in the elderly, and few children under age 10 years and almost no children under age 5 years are affected. 3,4 Data collected by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) on the occurrence of CRPS in patients with nerve injury and paralysis found CRPS develops in roughly 2 percent to 5 percent of patients who experienced peripheral nerve injury and roughly 12 percent to 21 percent of patients with hemiplegia (a form of paralysis that affects one side of the patient’s body).3

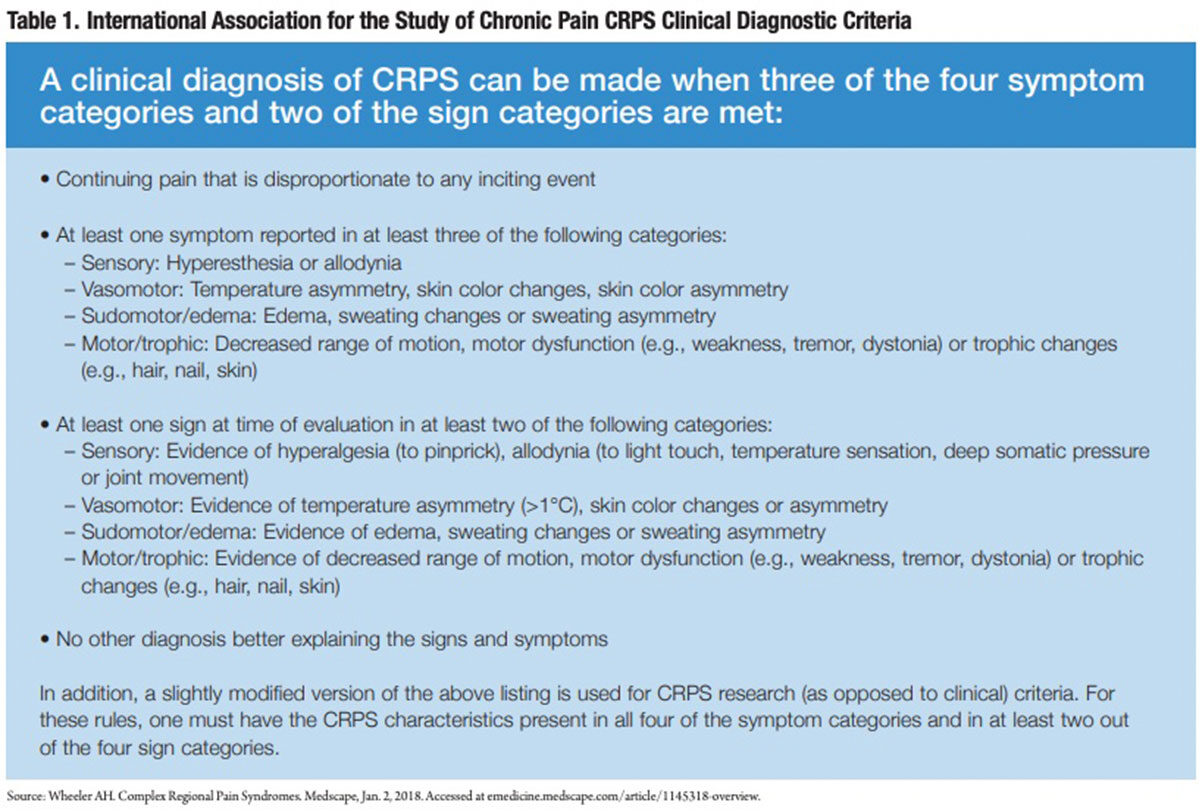

While the National Organization for Rare Disorders and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently designated CRPS a rare disease, meaning there are fewer than 200,000 cases in the U.S., the exact number of persons affected by CRPS today is not known due to a lack of understanding about it in the medical community — despite criteria explicitly defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (Table 1). 5 As such, increased awareness is needed about the real facts behind this disease.

Separating Myth from Fact

Myth: CRPS is a new and rare disease.

Fact: CRPS was first written about by Silas Mitchell Weir, MD, and colleagues during the Civil War. Dr. Weir, a U.S. Army contract physician who treated soldiers with gunshot wounds, described in his book Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves pain that persisted long after bullets were removed from the bodies of soldiers. He noted the pain was characteristically of a burning nature, and named it causalgia (Greek for burning pain), which he attributed to the consequences of nerve injury. Since that time, many other physicians have written about CRPS, calling it post-traumatic dystrophy, shoulder-hand syndrome and RSD.6

As stated previously, while FDA has declared CRPS a rare disease, some studies provide evidence that CRPS is not rare at all, especially CRPS type I. A Korean study showed 42 of 477 (8.8 percent) surgically treated wrist fracture patients developed CRPS type I, specifically among females with a high-energy wrist trauma or a severe communicated fracture. A Dutch study reported similar results with 42 of 596 (7 percent) fracture patients developing CRPS type I following emergency room treatment using the Harden and Bruehl diagnostic criteria. Yet, if the IASP criteria had been applied in the study, 289 of the same 596 fracture patients (48.5 percent) would have been deemed to have CRPS type I after treatment. And, in 2015, an Italian study reported CRPS occurred in anywhere from 1 percent to 37 percent of all fractures following orthopedic surgery, depending on the severity of the fracture.7

Myth: CRPS is a psychiatric disorder.

Fact: There is some debate about whether CRPS is a legitimate chronic pain condition versus a result of a patient’s psychiatric state. But, studies show patients with CRPS undergo physical changes to the nervous system and bones, joints, muscles and nerves in the affected area, making CRPS a purely psychosomatic disorder highly unlikely.8 Indeed, common features of CRPS are very visible, including:4

- Changes in skin texture on the affected area (it may appear shiny and thin)

- Abnormal sweating pattern in the affected area or surrounding areas

- Changes in nail and hair growth patterns

- Stiffness in affected joints

- Problems coordinating muscle movement, with decreased ability to move the affected body part

- Abnormal movement in the affected limb, most often fixed abnormal posture (dystonia), but also tremors in or jerking of the limb

Myth: CRPS is caused only by major injuries.

Fact: Actually, in more than 90 percent of cases, CRPS is caused by trauma or injury, the most common of which are fractures, sprains/strains, soft tissue injury (burns, cuts, bruises), limb immobilization (such as being in a cast), surgery or even minor medical procedures such as a needlestick.4 Of course, CRPS can also be caused by a major trauma or even a heart attack or stroke.9

What is unclear is why some people develop CRPS while others who experience similar trauma do not. One theory suggests pain receptors in the affected body part become responsive to catecholamines (a family of nervous system messengers). In animal studies, norepinephrine (a catecholamine released from sympathetic nerves) acquires the capacity to activate pain pathways after tissue or nerve injury.10 Another theory is CRPS is caused by an immune response. Individuals with CRPS have high levels of cytokines (inflammatory chemicals) that contribute to redness, swelling and warmth reported by many patients. In fact, CRPS is more common in individuals with other inflammatory and autoimmune conditions.4

Another cause of CRPS is genetics since rare family clusters have been reported. And, in some cases, CRPS develops without any known injury, but by an infection, blood vessel problem or entrapment of nerves causing an internal injury.4

Myth: CRPS types I and II have different symptoms.

Fact: The only difference between CRPS types I and II is the known cause. As stated earlier, if nerve injury is confirmed, it is known as CRPS type II, whereas if there is no confirmed nerve injury, it is known as CRPS type I.

Both types of CRPS have four main symptoms:2

- Constant chronic burning pain that is usually significantly greater than the original event or injury. While the affected area may feel cold to the touch, it feels to patients as though it is on fire. In addition, patients experience allodynia, which is an extreme sensitivity to touch, sound, temperature and vibration.

- Inflammation that can affect the appearance of the skin, bruising, mottling, tiny red spots, shiny, purplish look and skin temperature that can cause excessive sweating.

- Spasms in blood vessels (vasoconstriction) and muscles of the extremities.

- Insomnia and emotional disturbance that can include major changes to the limbic system such as short-term memory problems, concentration difficulties, sleep disturbances, confusion, etc.11 Other symptoms can include changes in nail and hair growth patterns, stiffness in affected joints and problems coordinating muscle movement, with decreased ability to move the affected body part.4

Myth: CRPS will not spread from its original location.

Fact: The American Journal of Medicine reports that spread of CRPS has been recognized since 1976.12 In fact, wherever there is a nerve, it can spread. In 70 percent or more of CRPS cases, pain starts in one part of the body and then spreads depending on the type of the original injury, treatments used, medical history and subsequent injuries. In most cases, it follows very specific paths such as from hand to arm or foot to leg. But, it can also spread from one side to another such as from the left foot to right foot or right hand to left hand. In addition, it can spread up the arm from the hand in what was once referred to as shoulder-hand syndrome.13 In about 8 percent to 10 percent of cases, it can become systemic (body wide),11 but this is more likely to happen when a spinal injury is involved.12 In worst cases, it affects completely healthy internal organs as well.14

Myth: CRPS resolves itself quickly.

Fact: There is debate concerning this myth, too. The prognosis for people with CRPS varies from person to person. Spontaneous remission does occur in some, but in others it persists for years. A recent systematic review of CRPS found evidence to suggest this discrepancy may “be due to a substantial number of cases resolving with limited or no specific intervention early in the course of the condition, with a smaller subset of more persistent cases being seen in tertiary care pain clinics.” For example, one study followed 30 patients with post-traumatic CRPS without treatment for an average of 13 months that found CRPS resolved in 26 of the 30 patients (the other four patients were withdrawn from the study to be given treatment). Another prospective study of 60 consecutive patients with tibial fracture who underwent standard care found 14 of the 18 patients diagnosed with CRPS at bone union were free of CRPS at one-year follow-up. However, researchers did note that neither of the studies used the IASP diagnostic criteria, which may have influenced the results.

In contrast, the same systematic review found much lower resolution rates in chronic CRPS patients even with specialty pain care. In one study of 102 patients over an average six-year follow-up, 30 percent reported resolution using the IASP criteria, 16 percent reported progressive deterioration, and the remaining 54 percent reported stable symptoms.15 In the Dutch study mentioned earlier, all patients who developed CRPS type I after fracture and treatment still had ongoing severe pain and other symptoms that persisted even at one-year follow-up.7

Myth: CRPS pain cannot be treated with opioids.

Myth: CRPS pain cannot be treated with opioids.

Fact: This myth is also debated due to the potentially harmful effects of opioids, as well as results from only one small randomized controlled trial of 43 patients conducted to determine opioids’ efficacy, which showed no significant analgesic effects of sustained release morphine (90 mg per day) over eight days.15 However, opioids are an effective treatment for many pain conditions. Unfortunately, no long-term studies of oral opioid use in treating neuropathic pain, including CRPS, have been performed. Even so, most experts believe opioids should be given as part of a comprehensive pain treatment program for CRPS. And, they should be prescribed immediately if other medications do not provide sufficient analgesia.16

Today, there is a lack of information about the pathophysiology of CRPS, and there are no consistent objective diagnostic criteria, which makes clinical trials that demonstrate effective therapies difficult to perform. As such, it is generally agreed CRPS must be treated with a multidisciplinary approach with the goal to control pain, with best results if treatment begins early when symptoms begin. A combination of therapies is typically necessary, including medications, physical and occupational therapy, interventional procedures, and psychosocial/behavioral management.17

While no drug is approved by FDA to treat CRPS, several classifications of medications are reported to be effective. However, it should be noted that no single drug or combination of drugs works for every person. Medications to treat CRPS include bisphosphonates (e.g., high-dose alendronate or intravenous pamidronate); nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., over-the-counter aspirin, ibuprophen and naproxen); corticosteroids that treat inflammation/swelling and edema (e.g., prednisolone and methylprednisolone); drugs initially developed to treat seizures or depression now known to be effective for neuropathic pain (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline, nortriptyline and duloxetine); botulinum toxin injections; opioids (e.g., oxycodone, morphine, hydrocodone and fentanyl); N-methyl-D aspartate receptor antagonists (e.g., dextromethorphan and ketamine); and topical local anesthetic creams and patches (e.g., lidocaine).4

Physical therapy can help to keep the painful limb or body part moving and can improve blood flow and lessen circulatory symptoms. It can also improve the affected limb’s flexibility, strength and function. Occupational therapy can help individuals learn new ways to work and perform daily tasks.4

Interventional pain management procedures are often used when conservative treatment options fail to provide adequate pain relief and restoration of function. These procedures include sympathetic nerve blocks, chemical and surgical sympathectomy, intravenous regional anesthesia, intravenous infusion, spinal cord stimulation, intrathecal medication and amputation.18

Psychotherapy is recommended because CRPS is often associated with profound psychological symptoms, including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, all of which heighten the perception of pain and make rehabilitation efforts more difficult.4

Lastly, there are a number of emerging treatments:4

- In a small trial in Great Britain, 13 patients with CRPS who did not respond well to other treatments were given low-dose intravenous immune globulin for six months to 30 months. Results showed a greater decrease in pain scores than those receiving saline during the following 14 days after infusion.

- In patients who have not responded well to other treatments, intravenous ketamine (a strong anesthetic) in low doses for several days to either substantially reduce or eliminate the chronic pain of CRPS is shown to be useful.

- Several studies have demonstrated reduced pain with the use of graded motor imagery therapy, which includes performing mental exercises such as identifying left and right painful body parts while looking into a mirror and visualizing moving those painful body parts without actually moving them.

- Alternative therapies also sometimes work, including behavior modification, acupuncture, relaxation techniques and chiropractic treatment.

Dispelling the Myths Now

The pain is all too real for patients suffering from CRPS, evidenced by visible signs and symptoms. Unfortunately, little is known about the condition, and little research has been conducted due a lack of understanding about the physiological processes associated with it.

Fortunately, there are studies and organizations working to overcome these obstacles to help patients. Currently, a number of clinical trials are being conducted, including a PhaseII trial of an oral non-opioid investigational medication and another investigating a medical device to manage pain associated with CRPS. Another promising therapy (Neurotropin) used extensively in Japan to treat CRPS and other painful conditions is being clinically studied by NINDS.19 IASP has instituted a special interest group on CRPS as a forum for members to engage in free and frank communication on the diagnosis and management of CRPS, bring focus to new developments, and assimilate the views of the different medical disciplines and patient reports about pain and the sympathetic nervous system.20

The designation of CRPS as an official rare disease in 2014 also holds promise. It could provide strong incentive for new drug development for this disease since FDA will accept clinical trials with fewer patients, making them more feasible, quicker and cheaper for manufacturers. In fact, the designation spurred a CRPS clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of neridronate, a new bisphosphonate that has been shown to significantly reduce pain compared to placebo, which led to the drug’s approval in Italy, China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.21 A second clinical trial of the drug is currently recruiting.22

It is hoped that between ongoing research and the rare disease designation, more will be learned about this painful condition, and improved treatments will become available.

References

- Personal CRPS/RSD Story: Samantha Reeb. Burning Nights, April 8, 2015. Accessed at www.burning nightscrps.org/personal-crps-rsd-story.

- American RSDHope. CRPS Overview/Description. Accessed at www.rsdhope.org/what-is-crps1.html.

- RSD Guide. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Accessed at rsdguide.com/crps.

- National Institutes of Health. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Fact Sheet. Accessed at www.ninds.nih.gov/ Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Complex-Regional-Pain-Syndrome- Fact-Sheet.

- American RSDHope. CRPS Patients — How Many Are There in the United States? Accessed at www.rsdhope.org/crps—how-many-victims-are-there-in-the-united-states.html.

- Promoting Awareness of RSD and CRPS in Canada. History of RSD/CRPS. Accessed at www.rsdcanada.org/parc/english/RSD-CRPS/history.htm.

- Pain Matters. CRPS Is Not ‘Rare’ in Fracture Patients, April 26, 2017. Accessed at painmatters.wordpress.com/2017/04/26/crps-is-not-rare-in-fracture-patients.

- RSDGuide. Psychosocial Effects from RSD. Accessed atrsdguide.com/symptoms-crps/psychosocial-effects-rsd.

- Transdermal Therapeutics. Facts about Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Accessed at www.transdermalinc.com/knowledge-base/articles/facts-about-complex-regional-pain-syndrome.

- GB Healthwatch. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Accessed at www.gbhealthwatch.com/complexregionalpainsyndrome-details.php.

- American RSDHope. CRPS Main Symptoms. Accessed at www.rsdhope.org/crps-symptoms.html.

- NSI StemCell. The 10 Most Common Questions About RSD. Accessed at nsistemcell.com/10-things-peopleask-about-rsd.

- American RSD Hope. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome FAQ’S. Accessed at www.rsdhope.org/crps-top-15-faqs.html.

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Fact Versus Fiction: The Truth Behind the CRPS Myths. Accessed at www.complexregionalpainsyndrome.net/fact-versus-fiction-the-truth-behind-the-crps-myths.html.

- Bruehl, S. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. British Medical Journal, 2015; 350:h2730. Accessed at rsds.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/CRPS-bruehl.pdf.

- Wheeler, AH. Complex Regional Pain Syndromes Treatment & Management. Medscape, Jan. 2, 2018. Accessed at emedicine.medscape.com/article/1145318-treatment?pa=ezsbwdqLgZwckaArniqd73LcpFzmr XMyXJJ9GrQCWaqiM8IECyIK%2B%2B5UqknbgyQOJyGvMX%2Fu%2BWdIXoARf%2FT0zw%3D%3D.

- Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Accessed at rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/4647/complex-regional-pain-syndrome.

- Stolzenberg, D, Chou, H, and Janerich, D. Chapter 9 — Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Interventional Treatment. In: Challenging Neuropathic Pain Syndromes. Accessed at www.sciencedirect.com/science/ article/pii/B9780323485661000097.

- Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association. RSDSA Provides Access to the Latest ResearchData on CRPS/RSD. Accessed at rsds.org/current-research.

- International Association for the Study of Pain. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Accessed at www.iasp-pain.org/SIG/CRPS.

- Marin, A. Shedding Light on Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Relief: Pain Research News, Insights and Ideas Brought to You by the IASP Pain Research Forum. Accessed at relief.news/shedding-light-on-complex-regional-pain-syndrome.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Safety of Intravenous Neridronic Acid in CRPS. Accessed at clinicaltrials.gov/ ct2/show/NCT02972359?term=neridronate&rank=3.