Making Sense of the Suicide Epidemic

Despite education and intervention efforts, suicide rates are at a global all-time high. As surviving loved ones suffer, public health officials struggle to find solutions to a problem that is both pervasive and complex.

- By Trudie Mitschang

FROM ACTOR Robin Williams and designer Kate Spade to celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain, high-profile suicides have dominated the headlines in recent years. These internationally publicized deaths put renewed focus on a tragedy that affects individuals of all ages, races, economic backgrounds and walks of life, often leaving friends and family members grappling with one anguished question: Why?

As researchers, educators and mental health professionals work to find answers, one fact is clear: Suicide is not just a problem in the United States; data indicate it’s become a global epidemic, especially among young people.1

Consider the following:

- Suicide is the second-leading cause of death globally for 15- to 29-year-olds.

- An alarming 78 percent of suicides occur in low- to middle income countries.

- The Japanese, despite being a very high-income country and having a population less than half the size of the United States, has the same number of suicides annually.2

Suicide and Mental Health

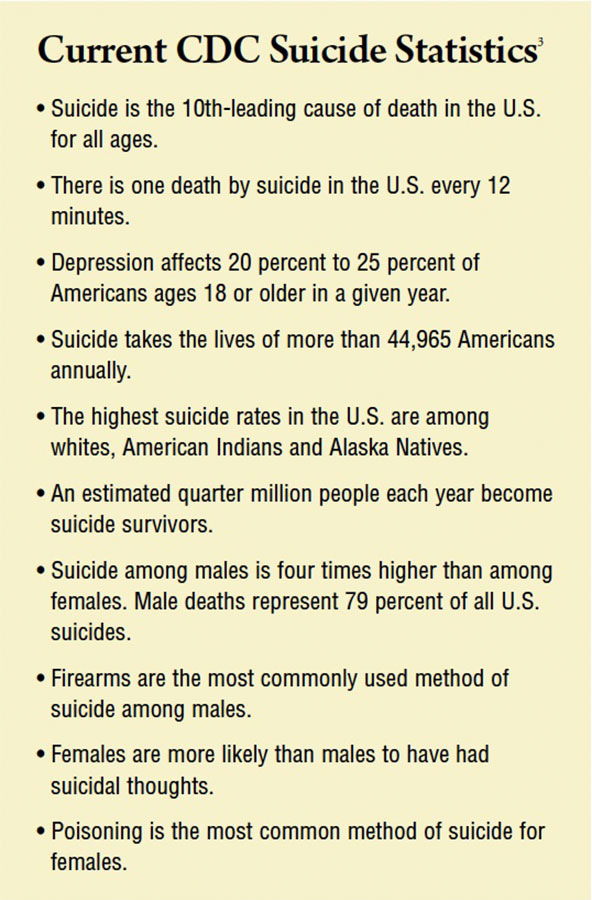

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the link between suicide and mental disorders — in particular, depression and alcohol abuse — is well-established, particularly in high-income countries like the U.S.

Professor Julie Cerel, president of the American Association of Suicidology, notes that access to better reporting standards could account for the global uptick in suicides, but she also points out that a lack of adequate funding for mental health research and preventive care is equally to blame. She highlights that as of 2018, only 10 states mandate suicide prevention training for health professionals.1 “Our mental health systems are just really struggling across the country,” she explains. “In terms of training mental health professionals, we’re not doing a great job.”

A recent CDC report highlights the complexity of suicide.3 While a mental health condition may be a contributing factor for many people, the report states “many factors contribute to suicide among those with and without known mental health conditions.” A relationship problem was the top factor contributing to suicide, followed by a personal crisis in the past or upcoming two weeks and problematic substance use. CDC reports about half of people who die by suicide do not have a known mental health condition. However, many of them may have been dealing with mental health challenges that had not been diagnosed or known to those around them.

When it comes to known risk factors, the American Psychiatric Association identifies the following:4

- Previous suicide attempt(s)

- A history of suicide in the family

- Substance misuse

- Mood disorders (depression, bipolar disorder)

- Access to lethal means (e.g., keeping firearms in the home)

- Losses and other events (for example, the breakup of a relationship or a death, academic failures, legal difficulties, financial difficulties, bullying)

- History of trauma or abuse

- Chronic physical illness, including chronic pain

- Exposure to the suicidal behavior of others

In some cases, a recent stressor or sudden catastrophic event or failure can leave people feeling desperate, unable to see a way out, and becomes a “tipping point” toward suicide.

Dealing with the Stigma

As with any form of mental illness, one of the biggest barriers to preventing suicide is stigma, which prevents at-risk individuals from seeking help. Additionally, while many people have the mistaken notion that talking about suicide causes it to happen more frequently, statistics do not support this notion — all the more reason mental health professionals advocate for a shift in thinking that will remove the stigma surrounding both suicide and mental illness. “Since we can’t see a mental illness in the same way we can see a broken bone or cancer cells, there is this belief that these illnesses are not ‘real,’ or at the very least are not ‘medical’ illnesses,” says Alexa Moody, founder and executive director of Please Live, a nonprofit dedicated to raising awareness of mental illness and preventing suicide. “This simply isn’t true. You can actually see the differences on brain scans.”5

For example, a diagnosis of clinical depression is marked by imbalanced chemicals in the brain that lead to feelings of unhappiness or a lack of fulfillment. “When these chemicals are off-balance, those emotions are difficult or sometimes impossible to achieve, so you take medicine to correct the chemical imbalance,” Moody says. “It’s the same as someone who is a diabetic; their body is not producing the correct amounts of insulin, so they take medication to correct that imbalance.”

That mental illness isn’t legitimate is just one myth in this field. Another, Moody says, is that talking about suicide will “plant the idea” in someone’s head. “This misconception is commonly shared by adults, school administrators, parents and community providers,” she says, adding that a refusal to talk about it ends up making the suicidal person feel alone and misunderstood, potentially making suicidal thoughts worse. On the other hand, with early intervention, many people report not having suicidal thoughts again. “We must address suicide and mental illness, and address it frankly and factually, for people to feel comfortable to get the help they need.”

As a mental illness survivor herself, Moody has a message of hope for others who may be suffering: With proper treatment, most people can and will get better. “Wellness and recovery are possible,” she explains, “and you don’t have to live with depression, anxiety or suicidal thoughts for the rest of your life.”5

The Fatal Link Between Suicide and Guns

When looking at the disparity between suicide and attempted suicide rates, research shows that whether attempters live or die depends in large part on the ready availability of highly lethal means, especially firearms. National data indicate that while guns are not the most popular means of taking one’s life, they are the most deadly. Statistics show 85 percent of attempts with a gun are fatal, compared with 69 percent for hanging and 2 percent for self-poisoning.6

A study by the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) of all 50 U.S. states reveals a powerful link between rates of firearm ownership and suicides. Based on a survey of American households conducted in 2002, HSPH Assistant Professor of Health Policy and Management Matthew Miller, Research Associate Deborah Azrael, and colleagues at the School’s Injury Control Research Center (ICRC) found that in states where guns were prevalent (as in Wyoming, where 63 percent of households reported owning guns), rates of suicide were higher. The inverse was also true: Where gun ownership was less common, suicide rates were also lower.6

The simple fact is few can survive a self-inflicted gunshot wound. In response to these concerns, ICRC’s Catherine Barber launched Means Matter, a campaign that asks the public to help prevent suicide deaths by adopting practices and policies that keep guns out of the hands of vulnerable adults and children. Barber, who co-directed the National Violent Injury Statistics System, has also developed free, self-paced, online workshops to help public officials, mental health service providers and community groups put together suicide prevention programs and policies.

Because suicide decisions are often made impulsively, access to firearms can mean the difference between life and death. An investigation by the New Hampshire medical examiner’s office showed nearly one in 10 suicides by firearms from 2007 to 2009 involved a weapon that was purchased or rented the preceding week — often within just a few hours.6 Guns, then, take what is often an ambivalent decision and turn it into an irrevocable one.

But what about the argument that people who are stopped from killing themselves today just find another way to complete the act later? Some undoubtedly will, but studies show the majority of survivors do not. The period of greatest vulnerability seems to be in the first year after an attempt, a time when treatment for those who try to end their life is critically important.

Spotlight on Education and Prevention

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) offers a variety of programs designed to raise awareness about suicide. Headquartered in New York, the organization was founded in 1987 with a mission to “give those affected by suicide a nationwide community empowered by research, education and advocacy to take action against this leading cause of death.” AFSP has local chapters in all 50 states with programs and events nationwide. Among its many initiatives, AFSP launched Out of the Darkness Community Walks to give people the courage to open up about their own struggle or loss, and the platform to eradicate the shame associated with suicide and mental illness. The organization also spearheads student-specific campus walks at colleges and high schools, and 16-mile overnight walks in cities across the country.7

The American Psychological Association (APA) is another

organization that has been actively working to shift public policy

to address suicide risk. Its efforts have focused on increasing access to care, including screening for depression, suicide and other mental health concerns; ensuring insurance coverage for prevention; increasing the number of trained healthcare professionals, including psychologists and other mental health professionals, and effective peer services; and increasing acute treatment resources by expanding Medicaid coverage for short-term acute inpatient stays.8

On April 21, 2018, APA joined organizations such as The Trevor Project, The Jed Foundation and the American Association of Suicidology in co-sponsoring the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention’s first annual Rally to Prevent Suicide. More than 500 individuals participated in the event on the steps of the Capitol, urging members of Congress to prioritize suicide research and community behavioral health clinic funding, as well as pass H.R. 2345, the National Suicide Hotline Improvement Act, which would create a three-digit emergency number for individuals experiencing a mental health crisis. “Suicide, like so many tragedies, is the direct result of despair, and there is only one cure for despair — hope,” said APA member Joel A. Dvoskin, PhD, ABPP. “It is my hope that our political parties can join together in a bipartisan effort to give people in the most acute despair some measure of hope for a better life — by improving the services that are provided.”

What the Future Holds

Suicide is a complex public health crisis with no easy solutions. In a recent report titled National Strategy for Suicide Prevention Implementation,9 three federal departments outlined their alliance aimed at suicide prevention efforts. According to the report, the U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs have partnered in a significant collaborative effort with goals and objectives that include integrating and coordinating suicide prevention activities across multiple sectors and settings; establishing effective, sustainable and collaborative suicide prevention programming at the state/territorial, tribal and local levels; and sustaining and strengthening collaborations across federal agencies to advance suicide prevention. The initiative also hopes to increase knowledge of the warning signs for suicide and connect individuals in crisis with assistance and care.9

In a summary statement, former U.S. Surgeon General Regina Benjamin said, “Reducing the number of suicides requires the engagement and commitment of people in many sectors in and outside of government, including public health, mental health, healthcare, the Armed Forces, business, entertainment, media and education.”

References

- Prasad R. Why U.S. Suicide Rate Is on the Rise. BBC News, June 11, 2018. Accessed at www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44416727.

- World Health Organization. Suicide Data. Accessed at www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide Rates Rising Across the U.S. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0607-suicide-prevention.html.

- American Psychiatric Association. Suicide Prevention. Accessed at www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/suicide-prevention.

- Future of Personal Health. The Key to Suicide Prevention is Less Stigma, More Conversation. Accessed at www.futureofpersonalhealth.com/prevention-and-treatment/the-key-to-suicide-prevention-is-less-stigma-more-conversation.

- Harvard School of Public Health. Guns and Suicide: A Fatal Link. Accessed at www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/magazine/guns-and-suicide.

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. You Can Fight Suicide. Accessed at afsp.org.

- The American Psychological Association. Accessed at www.apa.org.

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention Implementation Assessment Report, Feb. 9, 2018. Accessed at www.sprc.org/news/national-strategy-suicide-prevention-implementation-assessment-report.