Infectious Mononucleosis: The Best-Recognized Epstein-Barr Virus Infection

Typically treated with supportive care, this common human infection usually resolves in weeks with some symptoms persisting for months.

- By BSTQ Staff

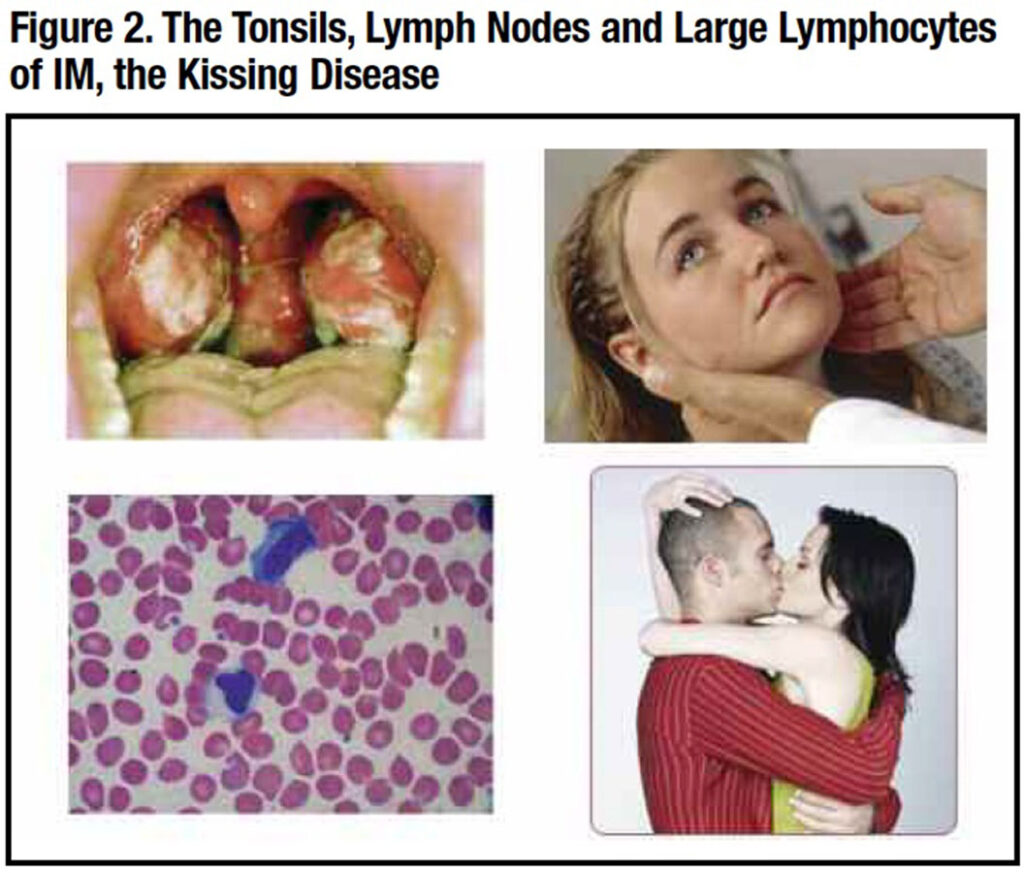

EPSTEIN-BARR VIRUS (EBV) disease is the most common chronic infection in humans, affecting nearly all older adults sometime in their lifetime.2 The best recognized EBV infection is infectious mononucleosis (IM), an acute febrile disease often seen in seronegative college students engaged in deep kissing, thus its familiar moniker “kissing disease” (Figure 2).3 Salivary secretion of the virus may persist for three or four months after recovery from IM, permitting its widespread dissemination on college campuses.

Early primary EBV infections are common in young children living in the tropics or in lower socioeconomic conditions.2 Such infections are generally mild or asymptomatic but lead to seroconversion with durable immunity to another primary EBV infection. Thus, IM is uncommon in these populations, and also in African-Americans.4,5

IM is only mildly contagious, as it is spread by oral secretions, not by respiratory droplets. It can also be transmitted by blood transfusion, organ transplants or, rarely, by maternal-fetal transmission.2

EBV and Its CD21 Receptor

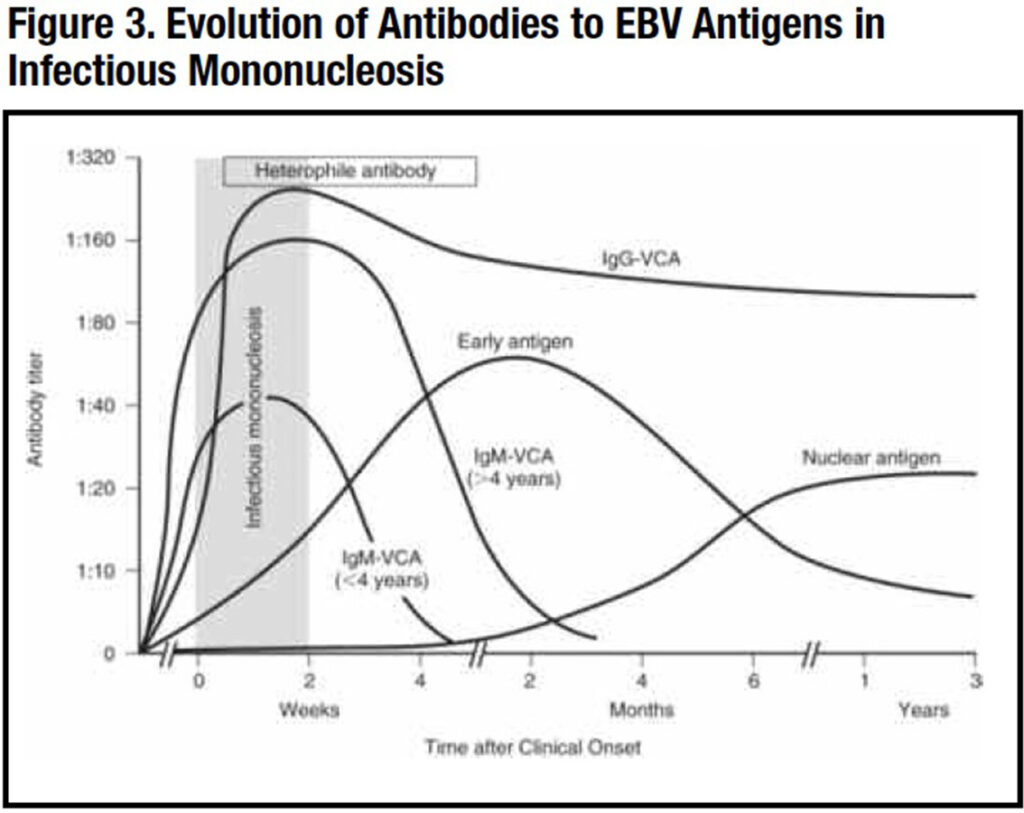

EBV is a herpes virus (human herpes virus-4) whose only natural reservoir is humans.2 The EBV receptor is the CD21 protein on the surface of B lymphocytes. Once EBV infection occurs, the virus remains forever in a latent state in B memory cells, resulting in lifetime seropositivity to the virus. Antibodies to the virus are directed at the viral capsid antigen (VCA), the nuclear antigen (EBNA) and the early antigen (EA), which appear in a characteristic sequence after an acute EBV infection (Figure 3).

B cells harboring the latent virus can become activated at any age to proliferate and release virus, usually following another illness, medications or stress. These secondary infections can be mild or severe and cause a myriad of illnesses.

The EBV CD21 receptor is also present on some nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. EBV entering the mouth attaches to these short-lived cells that proliferate and excrete virus into the saliva and infect local B cells that disseminate the virus throughout the body. They also stimulate the production of EBV-specific antibodies and CD8 cytotoxic T cells, the latter of which control the acute infection. Virus remains in the body forever as a latent infection in some memory B cells.

The ability of EBV to infect and immortalize B cells allows for the in vitro production of a permanent B cell line. These cells can be frozen, thawed and expanded to provide an unlimited source of a patient’s DNA for genetic tests.

Delineation of Infectious Mononucleosis

In 1887, Emil Pfeiffer, MD, of Wiesbaden, Germany, described a short-term febrile illness characterized by fever, sore throat and cervical adenopathy that sometimes occurred in families. He called this glandular fever.6 In 1920, Thomas Peck Sprunt, MD, and Frank Alexander Evans, MD, at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore identified a similar syndrome among close contacts and noted the presence of large atypical lymphocytes in the blood smear and coined it IM.7

Then, in 1924, John R. Paul, MD, and W.W. Bunnell, MD, at the Yale School of Medicine observed in the serum of IM patients agglutinated (stuck together to form a mass) sheep erythrocytes, labeling these heterophile antibodies.8 These antibodies persist for several weeks after an IM infection. This antibody became the standard diagnostic tool to diagnose the disease with an 85 percent to 90 percent specificity and sensitivity.9 It was later improved upon by a preabsorption step with guinea pig kidney cells and the use of horse erythrocytes instead of sheep erythrocytes, and is now known as the monospot test, which is used today.10

Discovery of Epstein-Barr Virus

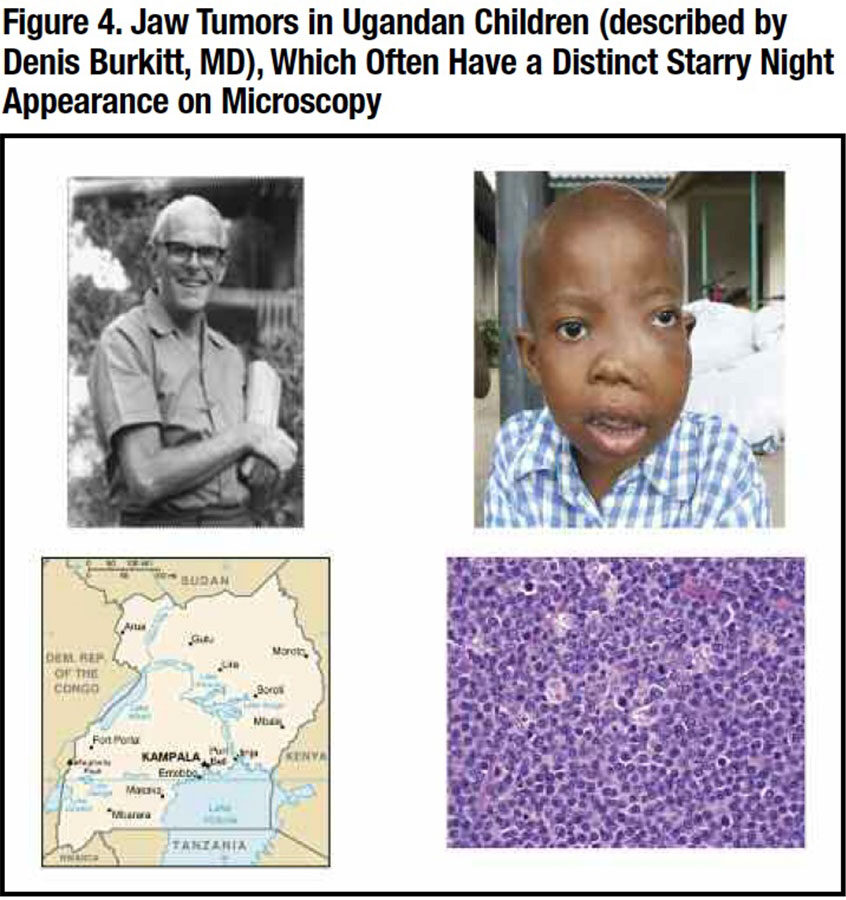

Despite its identification, the cause of IM remained a mystery that began to be unraveled in tropical Africa. In 1938, Denis Burkitt, MD, an English missionary doctor working in Uganda, noted several young children with prominent jaw tumors that on biopsy resembled a lymphoma (Figure 4).11 He thought this was an infection possibly spread by the malaria mosquito. This fatal illness became known as Burkitt’s lymphoma.

Twenty-six years later in 1964, Michael Epstein, CBE, FRS, FMedSci, and Yvonne Barr, PhD, of the United Kingdom were able to grow cells from a surgically removed Burkitt tumor.12 Using the electron microscope, they identified a viral particle resembling a herpes virus,13 which became known as the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

In 1966, Gertrude Henle, PhD, and Werner Henle, PhD, a husband and wife team of virologists in Philadelphia, developed an indirect immunofluorescent antibody test for EBV.14 They showed this antibody was present in patients with Burkitt’s lymphoma, but was also present in many normal individuals. It was also present in the blood of a laboratory worker who was recovering from IM. By good fortune, the worker had donated a blood sample before contracting IM, and this blood had no EBV antibodies. This suggested EBV was the cause of IM.15

Subsequent studies on many other IM patients validated this conclusion, solving the medical mysteries started in Germany in 1887 that continued in Uganda in 1938. A complete history of IM is available.16

Clinical Features

IM is particularly common among college students, 18 years to 24 years old.3 EBV is transmitted by close oral contact with someone secreting the virus in the saliva; viral secretion may continue for several months after an initial EBV infection.2

After an incubation period of two weeks to four weeks, the cardinal features of fever, pharyngitis and lymphadenopathy occur. Fatigue and myalgia are also common and may persist for several weeks after other symptoms subside.17,18 Persistent fatigue is more common in females and those with prior mood disorders.

Sore throat is common, usually associated with enlarged tonsils with a gray or white exudate mimicking a streptococcal infection (Figure 2). Palatal petechiae or hemorrhagic streaks may also be noted. Posterior cervical lymphadenopathy appears early, and the nodes are symmetric and tender. Lymphadenopathy in other areas of the body may occur, unlike the adenopathy of bacterial pharyngitis. Occasionally, lymphadenopathy is so severe that airway obstruction or a peritonsillar abscess may develop.

Splenic enlargement occurs in about half of the patients, usually lasting for three weeks. Splenic rupture is uncommon, but strenuous physical activity, especially contact sports, should be avoided until the illness has subsided and the spleen is no longer enlarged.

Maculopapular or urticarial rashes are not uncommon. They are often provoked by antibiotics, usually ampicillin or amoxicillin but sometimes by azithromycin, levofloxacin, and cephalosporins. The mechanism is not known, but it does not appear to be a true drug allergy since it does not recur with a repeat dose after the patient is well.

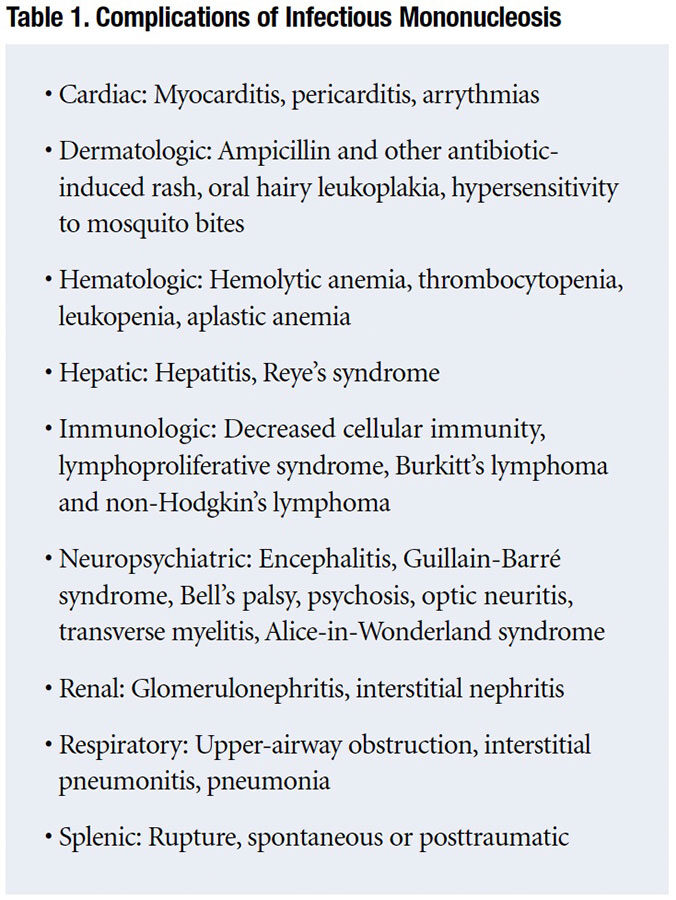

Neurologic syndromes associated with IM include Guillain-Barré syndrome, cranial nerve palsies, peripheral neuropathy, aseptic meningitis, encephalitis and the Alice-in-Wonderland syndrome described in the vignette.1

Less common manifestations may affect many other organ systems as presented in Table 1. Differential diagnosis includes streptococcal infections, acute cytomegalovirus or HIV infection, toxoplasmosis, lymphoma or hypersensitivity to a drug, particularly anticonvulsants or antibiotics.

Laboratory Features

Blood abnormalities include a leukocytosis due to an absolute lymphocytosis (e.g., greater than 4,500 cells/μl). Many of the lymphocytes are enlarged and atypical; these are CD8 cytotoxic cells directed against EBV-positive B lymphocytes.

Inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein) are often elevated, as are immune globulin levels, principally IgM. Autoimmune antibodies may be present such as the direct Coombs test, rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibody (ANA). Liver function tests are often elevated, indicating liver involvement.

The heterophile antibody or the monospot test is usually positive as are antibodies to viral antigens, including viral capsid antigen (VCA), nuclear antigen (EBNA) and early antigen (EA). These antibodies appear at different stages of the infection (Figure 3). Acute infection is associated with the appearance of IM antibodies to VCA (IgM-VCA) followed shortly by IgG-VCA and EA antibodies. Past infection is indicated by IgG-VCA without IgM-VCA antibodies.2

The presence of EBV in the blood as indicated by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test is indicative of current active EBV infection; its quantitation can be used to determine the severity and course of the disease.

Management

Isolation of patients is not necessary even though they may secrete virus in the saliva for several weeks.

Treatment of IM is usually supportive: rest, analgesics, adequate fluid and nutrition. Antivirals are of no proven value, even in severe cases. Corticosteroids are sometimes indicated if there is an associated hemolytic anemia, severe hepatitis or strikingly enlarged lymphadenopathy with respiratory or swallowing compromise.

Splenomegaly may be present in 50 percent of cases and subject to rupture. Therefore, strenuous exercise or contact sports should be avoided during the acute illness and until the spleen is no longer enlarged.

Patients can return to school or work as soon as they feel well. They are not contagious to everyday contacts, just to their kissing and sexual partners.

No vaccine is available.

Prognosis

Most patients eventually recover uneventfully and develop durable immunity to the virus. Acute symptoms resolve in two weeks to three weeks, but persistent fatigue may persist for several months. Chronic fatigue may be prolonged, particularly among women and those with a prior history of a mood disorder.

Reactivation of the virus from its latent state may occur years after primary infection. This may occur as a result of another illness or the use of a drug that suppresses cellular immunity. These disorders are multiple and a topic of another article.

Occasionally, the acute infection is followed by a chronic EBV infection with persistent viremia.19 This is a serious disease with a guarded prognosis. By contrast, persistent seropositivity without viremia is common and not a cause of chronic disease, including chronic fatigue syndrome.

References

- Copperman SM. “Alice in Wonderland” syndrome (metamorphopsia) as a Presenting Symptom of Infectious Mononucleosis in Children: A Description of Three Affected Young People. Clin Pediatr(Phila) 1977; 6:143.

- Castagnini LA and Leach CT. Epstein-Barr Virus in Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 8th edition. Edited by Cherry JC, et al. Elsevier (Phila) 2019; pp 1450-1471.

- Evans AS. Infectious Mononucleosis in University of Wisconsin Students: Report of a Five Year Investigation. Am J Hyg 1960,71:342.

- Nye FJ. Social Class and Infectious Mononucleosis. J Hyg Camb 1973. 71;145.

- Brodsky AE and Heath Jr CW. Infectious Mononucleosis: Epidemiologic Patterns at United States Colleges and Universities. Am J Epidemiol 1972,96: 87.

- Pfeiffer E. Drusenfieber. Jahrb f Kinderheilk 1869 29: 257.

- Sprunt TP and Evans FA. Mononucleosis Leukocytosis in Reaction to Acute Infectious (Infectious Mononucleosis). Johns Hopkins Hosp Bull 1920. 31;409.

- Paul JR and Bunnell WW. Classics in Infectious Diseases. The Presence of Heterophile Antibodies in Infectious Mononucleosis. Am J Med Sci 1932. Rev Infect Dis 1982. 4;1062.

- Evans AS, Niederman JC, Cenabre LC, et al. A Prospective Evaluation of Heterophile and Epstein–Barr Virus-Specific IgM Antibody Tests in Clinical and Subclinical Infectious Mononucleosis: Specificity and Sensitivity of the Tests and Persistence of Antibody. J Infect Dis 1975. 132,546.

- Basson V and Sharp AA. Monospot: A Differential Slide Test for Infectious Mononucleosis. J Clin Path 1969. 22;324.

- Burkitt D. A Sarcoma Involving the Jaws in African Children. Brit J Surg 1938. 46;218.

- Epstein MA and Barr YM. Cultivation in Vitro of Human Lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s Malignant Lymphoma. Lancet 1964. 1;252.

- Epstein MA, Achong, BG, and Barr YM. Virus Particles in Cultured Lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s Lymphoma. Lancet 1964. 1;702.

- Henle G and Henle W. Immunofluorescence in Cells Derived from Burkitt Lymphoma. J Bact 1966,91:1248.

- Henle G, Henle W, and Diehl V. Relation of Burkitt’s Tumor-Associated Herpes-Type Virus to Infectious Mononucleosis. Proc Nat Acad Sci 1968,59:94.

- Evans AS. The History of Infectious Mononucleosis. Amer J Med Sci 1974.267:189.

- Peter J and Ray G. Infectious Mononucleosis. Pediatr Rev 1988.19:278.

- Dunmire KA, Hogquist KA, and Balfour Jr, HH. Infectious Mononucleosis. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol 2015. 390; 211.

- Kimura H, Morishima T, Kinegame H, et al. Prognostic Factors for Chronic Active EBV Infections. J Infect Dis 2003.187;327.