Diagnosing and Treating Lyme Disease

While rare, Lyme disease can be debilitating and cause long-term damage due in part to delayed and missed diagnoses. However, there is hope of a vaccine in the future.

- By Jim Trageser

LYME DISEASE HAS been with us for centuries, if not longer. While today it is the most prevalent vector-borne disease in the United States (with 25,000 to 30,000 cases reported per year1), it was only identified as a specific infection in 1975. That year, doctors noticed a surge in reported cases of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis near the town of Lyme, Conn. Many of the patients also exhibited a distinctive rash that looked like a bulls-eye target, along with swollen lymph nodes, extreme fatigue and headaches. But it wasn’t until 1981 that researchers discovered the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi living in the gut of deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis) and were able to tie that to the Lyme disease outbreak in Connecticut six years earlier.

In the half-century since Lyme disease was first identified, researchers have gained tremendous knowledge of its progression and its long-term effects on patients. They’ve identified additional tick species that can serve as vectors, and they’ve expanded the known species of Borrelia bacteria that can cause Lyme disease.

After geneticists at Yale outlined the full genome of the bacteria that causes Lyme disease in 2017, they were able to infer that it has existed in North America for more than 60,000 years.2 An earlier study at the University of Bath found that the bacteria likely dates back to the most recent Ice Age in Europe.3 With this knowledge, other medical researchers found references to the symptoms of Lyme disease going back to the earliest European immigrants to North America. European researchers have found descriptions of those same symptoms on the continent as far back as the late 19th century.

Fortunately, the development of effective antibiotics has allowed physicians to treat Lyme disease, although long-term symptoms are not yet fully understood, nor do they always respond to treatment. And while the only approved vaccine was withdrawn from market due to disappointing sales over two decades ago, research on new vaccines continues.

What Is Lyme Disease?

Lyme disease is an infectious disease that can cause debilitating pain and result in significant tissue damage, but is rarely fatal. It can be caused by any one of 18 different species of Borrelia bacteria.4 The species found in Europe are distinct from those found in North America. In the eastern United States, the main vector is the deer tick, while a relative found on the west coast, the western black-legged-tick, Ixodes pacificus, can also transmit the disease.

There are two distinct life cycles at work in Lyme disease: the bacteria itself and the ticks that carry the bacteria from one warm-blooded host to another. Most species of Borrelia will reproduce in a small mammal or bird. Larger hosts, such as deer or humans, do not appear to be viable hosts for Borrelia to reproduce in.5 If an Ixodes tick feeds on a host, the bacteria can live in the tick but will not reproduce in the host due to the radically different biological environment. They do, however, move from the tick’s stomach to the salivary glands using a flagellum, where they are now ready to be transmitted to a new warm-blooded host to reproduce.6

The ticks go through a four-part reproductive cycle: eggs, larvae, nymph, adult. The larvae and nymphs both feed on a warm-blooded host to help them develop to the next stage. When an infected nymph or adult feeds again, it can pass the Borrelia bacteria to the next host. (Adult females that are infected will not pass the bacteria to their offspring.7)

While, as mentioned, about 25,000 to 30,000 cases are reported per year in the United States, it is not a mandatory reportable disease in most jurisdictions, so the true number is likely higher. It is more common in children whose play will take them into tall grasslands and wooded areas where ticks live. But hikers, farm workers, ranchers and other adults who spend time in areas of brush in the Midwest or northern reaches of the East Coast and West Coast are also at higher risk. The ticks that carry the bacteria that causes Lyme disease are at their most active in late spring, summer and early fall.

Symptoms and Progression of Lyme Disease

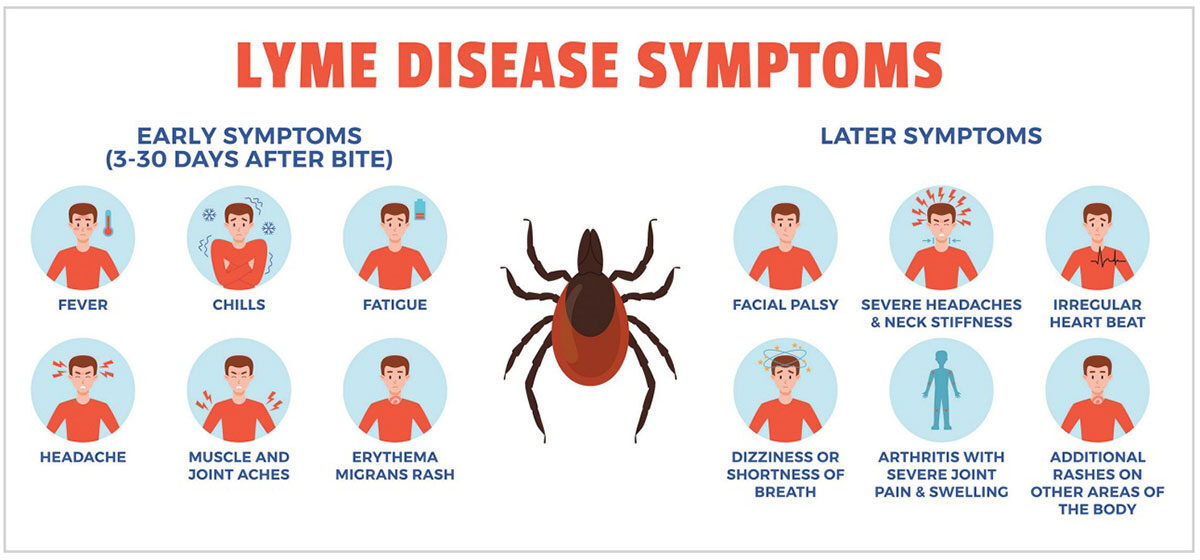

The first symptom of Lyme disease is a tick bite. But if it was a larvae or nymph, the bite may be too small to be noticed. A circular rash may spread from the point of the bite, but not all Lyme disease patients will develop the rash.

Other preliminary symptoms may include:8

- Headache

- Muscle pain

- Joint stiffness

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Swollen lymph nodes

This first round of symptoms is known as the early localized Lyme disease stage, and it generally lasts until three to four weeks after the tick bite.9 If untreated, the disease will progress to what is known as early disseminated Lyme disease, which can last up to three months. This stage may be marked by some or all of these symptoms:

- Rashes on different parts of the body

- Muscle weakness on the face

- Irregular heartbeat

- Pain and/or weakness in the hands or feet

- Eye pain or vision loss

- Back, hip or neck pain

The final stage can last for decades, and is known as late disseminated Lyme disease. Any of the previous stage symptoms may manifest, and they may dissipate and return. Arthritis may develop in the knees or other large joints.

If a person contracts Lyme disease in Europe, he or she may also exhibit swollen, discolored skin on the back of the hands or top of the feet, which may not manifest for many years after the initial infection.

Frustratingly, even those who have been successfully treated with antibiotics and have no active infection can develop symptoms similar to those of late disseminated Lyme disease. This is known as posttreatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS).10

Serious cases can cause damage to joints or other internal tissues, including the brain, leading to conditions known as chronic neurologic Lyme disease and neuropsychiatric Lyme disease. In more serious cases, this can lead to meningitis, encephalopathy, encephalitis and/or encephalomyelitis, all of which can lead to significant cognitive impairment or even psychosis.10 Less severe symptoms may include trouble remembering, numbness in the feet or hands, chronic fatigue and depression.

Diagnosing Lyme Disease

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a twopart blood test for Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies (both tests can be performed on a single sample).11 The first test is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). If the first test result is positive (abnormal), a second test (Western blot) should be run.12

CDC urges physicians not to request an assay unless the symptoms are consistent with Lyme disease and the individual would have had the opportunity to be bitten by a tick. The agency also cautions that a blood test can return a false negative if the blood is drawn within the first four to six weeks of infection, and it can also indicate a false positive if the patient has Epstein-Barr virus, syphilis, rheumatoid arthritis or relapsing fever.

Unfortunately, Lyme disease can be difficult to diagnose for several reasons. First, its symptoms mimic a number of other diseases. Second, the circular red rash, known as erythema migrans, fails to appear in at least one-quarter of people who are actually infected with Lyme bacteria. Third, current diagnostic tests do not always detect early Lyme disease since antibodies take time to rise to detectable levels.13

A study published in Healthcare in 2018 that analyzed 3,903 individuals registered with MyLymeData found that “more than half (51 percent) reported that it took them more than three years to be diagnosed and roughly the same proportion (54 percent) saw five or more clinicians before diagnosis.” What’s more, the study found there was a delay in diagnosis even when patients had an early onset of symptoms: “Diagnostic delays occurred despite the fact that 45 percent of participants reported early symptoms of Lyme disease within days to weeks of [tick] exposure.” Findings showed the reasons for such delays included false negative lab tests (37 percent) or positive test results “that were dismissed as ‘false-positives’ (13 percent).” In addition, “the majority of patients (72 percent) reported being misdiagnosed with another condition prior to their Lyme diagnosis.”14 (See “Lyme Disease: A Patient’s Perspective” and “Lyme Disease: A Physician’s Perspective” on pages 48 and 49.)

Treating Lyme Disease

Even before Lyme disease was identified, physicians had noted that the symptoms later associated with the disease were eased by the use of penicillin. Cases that are caught early can be effectively treated with antibiotics to stop the bacterial infection before it spreads throughout the body. Doxycycline and amoxicillin are the most common treatments for early stages of Lyme disease, and they will address the rash in addition to the bacterial infection.9

If Lyme disease is not diagnosed until later stages, then symptoms may also need to be addressed, as well as the underlying bacterial infection. In later stages, the antibiotics may need to be administered intravenously to help them spread throughout the body. Whether oral or intravenous, the antibiotics may need to be taken for several weeks or even a month. For patients with joint or muscular pain, the pain can be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Patients who suffer from an irregular heartbeat as a result of Lyme disease may need a temporary pacemaker until the antibiotics decrease the infection.15

Severe or advanced cases may call for a stronger antibiotic such as ceftriaxone.

There is some indication that intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) can be effective in treating PTLDS since there seems to be an immunological component to the condition.16 Researchers write that while there is enough clinical evidence to warrant further study, the overall effectiveness and the actual mechanism of how IVIG works are not yet known.17

Preventing Lyme Disease

The best treatment for Lyme disease is to not contract it in the first place. Patients in high-risk areas should be advised to wear long sleeves and pants, with cuffs than can be sealed, or to tuck pant legs into socks. Insect repellent should also be applied to both exposed skin and all external clothing. When returning from the outdoors in high-risk areas, all clothing should be immediately removed, and the skin should be inspected for ticks, removing any that are found.18

To date, there has only been one vaccine for Lyme disease — LYMERix— that was discontinued in 2002 due to low sales.19 But, even that inoculation lost effectiveness over time, so anyone who received LYMERix before it was removed from market is no longer protected against Lyme disease.

Ongoing Research

Physicians and researchers still do not understand why some patients who have received antibiotics and show no signs of an active infection go on to develop PTLDS.

One new treatment that has been granted a patent (but has not yet entered clinical trials) would not only detect an active infection, but offers the promise of being able to determine when the infection has resolved. (Current tests often return a false positive even after the infection has ended since the body is still producing antibodies against the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria.)

Case Integrative Health’s patent uses a different method of checking for infection by measuring the immune response to Borrelia burgdorferi antigens.20 Researchers at the company believe this method will provide a clearer picture of the state of infection, potentially preventing more patients from unknowingly progressing to late-stage Lyme disease if the initial round of antibiotics doesn’t quell the infection.

Among the roughly 100 clinical trials into Lyme disease listed on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) clinicaltrials.gov website is a new recombinant vaccine candidate, VLA15.21 Two randomized, observer-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center Phase II studies of VLA15 were conducted. Both studies included participants aged 18 to 65 years without recent history of Lyme borreliosis or tick bites. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 90 μg (study one only), 135 μg or 180 μg VLA15 or placebo by intramuscular injection at months zero, one and two (study one) or zero, two and six (study two). The primary endpoint for both studies was OspA-specific IgG geometric mean titres (GMTs) at one month after the third vaccination and was evaluated in the per-protocol population. Study findings showed the vaccine was safe, well-tolerated and elicited robust antibody responses, with no related serious adverse events or deaths.22 As of this writing, the vaccine is now in a Phase III trial titled VALOR (Vaccine Against Lyme for Outdoor Recreationists) that is evaluating it in individuals who have completed the primary vaccination series (three doses) of the vaccine. In this study, participants are being monitored for the occurrence of Lyme disease cases until the end of the Lyme disease season in 2024. Subject to positive Phase III data, Pfizer/Valneva aim to submit a biologic license application to FDA in 2026.23

Other clinical trials are looking into new blood tests to more accurately test for Lyme disease, as well as several novel approaches to the use of physical therapy to help patients recover from joint damage arising from late-stage Lyme disease.

Looking Ahead

While VLA15 shows promise as a potential vaccine, patients will continue to contract Lyme disease in the immediate future. Early detection and effective treatment are the best courses for keeping Lyme disease from progressing to a stage that inflicts significant damage. Educating patients in high-risk areas about how to protect themselves while outdoors remains the best preventive measure at this time.

References

1. Shapiro, ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme Disease). Pediatrics In Review, 2014 Dec; 35(12):500–50. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5029759.

2. IGeneX. TheHistory of LymeDisease. Accessed atigenex.com/ticktalk/the-history-of-lyme-disease.

3. Wellcome Trust. Lyme Disease Bacterium Came From Europe Before Ice Age. ScienceDaily, June 30, 2008. Accessed at www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/06/080629142805.htm.

4. IGeneX. An Overview of the Types of Borrelia That Cause Lyme Disease. Accessed at igenex.com/tick-talk/an-overview-of-thetypes-of-borrelia-that-cause-lyme-disease.

5. Radolf, J, Caimano, M, Stevenson, B, and Hu, L. Of Ticks, Mice and Men: Understanding the Dual-Host Lifestyle of Lyme Disease Spirochaetes. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2012; 10:87–99. Accessed at www.nature.com/articles/nrmicro2714.

6. Sultan, S, Stewart, P, Manne, A, et al. Motility Is Crucial for the Infectious Life Cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infection and Immunity, 2013 Jun; 81(6): 2012–2021. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3676011.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How Lyme Disease Spreads. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/lyme/causes/index.html.

8. Mayo Clinic. Lyme Disease. Accessed at www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/lyme-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20374651.

9. Cleveland Clinic. Lyme Disease. Accessed at my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/11586-lyme-disease.

10. Ada. Late Lyme Disease, Feb. 15, 2022. Accessed at ada.com/conditions/late-lyme-disease.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated CDC Recommendation for Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease, Aug. 16, 2019. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6832a4.htm.

12. Mount Sinai. Lyme Disease Blood Test. Accessed at www.mountsinai.org/health-library/tests/lyme-disease-blood-test.

13. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Lyme Disease Diagnostics Research. Accessed at www.niaid.nih.gov/diseasesconditions/lyme-disease-diagnostics-research.

14. Johnson, L, Shapiro, M, and Mankoff, J. Removing the Mask of Average Treatment Effects in Chronic Lyme Disease Research Using Big Data and Subgroup Analysis. Healthcare, 2018; 6(4):124. Accessed at www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/6/4/124.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Care and Treatment of Lyme Carditis, May 15, 2024. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/lyme/hcp/clinical-care/lyme-carditis.html.

16. Wong, K, Shapiro, E, and Soffer, G. A Review of Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome and Chronic Lyme Disease for the Practicing Immunologist. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology, 2022 Feb;62(1):264-271. Accessed at pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34687445.

17. Cross, A, Bouboulis, D, Jones, C, and Shimasaki, C. Case Report: PANDAS and Persistent Lyme Disease with Neuropsychiatric Symptoms: Treatment, Resolution, and Recovery. Frontiers in Psychiatry, February 2021. Accessed at www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.505941/full.

18. Penn Medicine. Lyme Disease. Accessed at www.pennmedicine.org/for-patients-and-visitors/patient-information/conditions-treated-a-to-z/lyme-disease.

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme Disease Vaccine. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/lyme/about/lyme-disease-vaccine.html.

20. Drake, K. New Test Could Help Monitor Lyme Disease Treatment. Healthnews, Sept. 27, 2024. Accessed at healthnews.com/news/new-lyme-disease-test.

21. ClinicalTrials.gov. Phase 2 Study Of VLA15, A Vaccine Candidate Against Lyme Borreliosis, In a Healthy Pediatric and Adult Study Population, July 9, 2024. Accessed at clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04801420?cond=Lyme%20disease&rank=5.

22. Bézay, N, Wagner, L, Kadlecek, V, et al. Optimisation of Dose Level and Vaccination Schedule for the VLA15 Lyme Borreliosis Vaccine Candidate Among Healthy Adults: Two Randomised, ObserverBlind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicentre, Phase 2 Studies. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2024, Sept;24(9):1045-1058. Accessed at www.thelancet.com/article/S1473-3099(24)00175-0/abstract.

23. Phase 3 VALOR Lyme Disease Trial: Valneva and Pfizer Announce Primary Vaccination Series Completion. Pfizer press release, July 17, 2024. Accessed at www.pfizer.com/news/pressrelease/pressrelease-detail/phase-3-valor-lyme-disease-trial-valneva-and-pfizer.