Diagnosing and Treating Infant Botulism

Since the approval of BabyBIG, the only treatment for this rare but life-threatening disease affecting infants mostly under 6 months, the mortality rate is now less than 15 percent.

- By Ronale Tucker Rhodes, MS

INFANT BOTULISM occurs globally and is now the most common form of human botulism in the United States.1 According to a StatPearls continuing education activity published in 2023 that reviewed the causes, pathophysiology and presentation of infant botulism, this rare disease is responsible for approximately 70 percent of all new botulism cases a year. In the United States, 1.9 of 100,000 live births yield approximately 77 new cases annually, and there is an equal distribution of males and females. However, Hispanics and Asian families have a higher incidence of infant botulism because of their use of herbal medications and raw honey.2

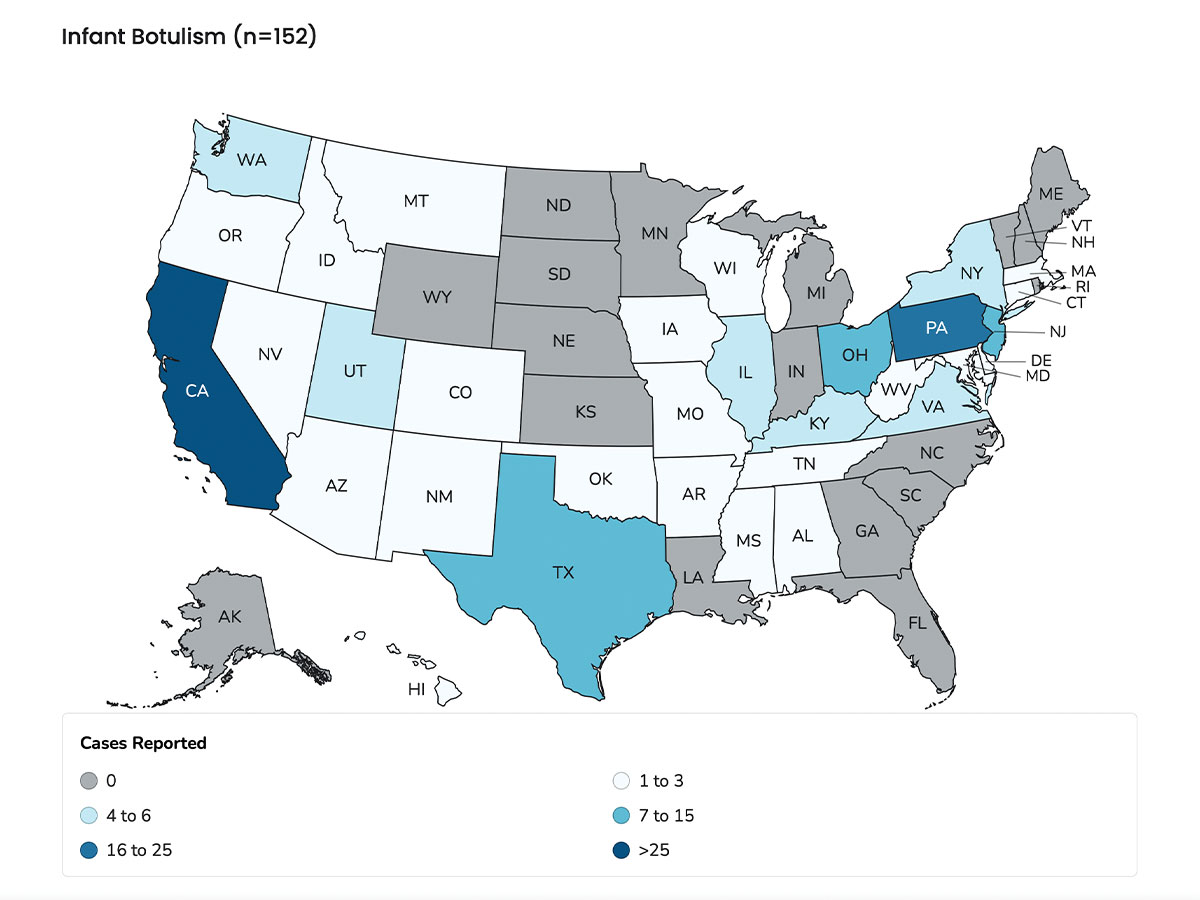

In 2019, the most recent statistics available in the U.S., state and local health departments reported de-identified data about 152 confirmed cases of infant botulism to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, all of which were laboratory-confirmed. Fortunately, no deaths were reported. The median age of infants was 4 months (range 2 weeks to 10 months), 57 percent (87) of whom were male.3 Mostly, infant botulism occurs in babies younger than 6 months.4

The disease was first recognized in 1976 by Stephen Soulé Arnon, MD, and colleagues after Dr. Arnon received a call about a paralyzed infant from Salinas, Calif. Through epidemiological and laboratory investigation, they collected the novel evidence that the baby’s digestive tract was colonized with Clostridium botulinum (C. botulinum), the bacterium that produces an exceptionally potent neurotoxin. As additional infants with acute weakness in California were detected throughout 1976, Dr. Arnon and his co-discoverers named the condition infant botulism, in contrast to botulism resulting from contaminated food or wounds.5

What Is Infant Botulism?

Infant botulism is an intestinal toxemia that results after spores of the bacterium C. botulinum or related species are swallowed and temporarily colonize an infant’s large intestine and produce botulinum neurotoxin. The neurotoxin binds to cholinergic nerve (nerves involved in motor control, including the muscles in the face, neck and tongue) terminals that sever intracellular proteins necessary for acetylcholine (a neurotransmitter that plays a role in memory, learning, attention, arousal and involuntary muscle movement) release.6

Causes and Prevention of Infant Botulism

Even though there are multiple ways to contract botulism, only three main serotypes are responsible for all of these infections: type A (predominantly found west of the Mississippi River), type B (predominantly found east of the Mississippi River) and type E (found in the Pacific Northwest with a preponderance in Alaska).2

According to an article published in Current Microbiology in 2024, “honey has been identified as the only well-known risk factor for infant botulism, despite a multitude of international environmental surveys isolating C. botulinum spores from ground soil, aquatic sediments and commonly available infant foods. Associations of infant botulism cases with confirmed sources of C. botulinum exposure have primarily implicated outdoor soil and indoor dust, as well as commonly ingested foods, including honey, dry cereals and even powdered infant formula. Yet the origin of infection remains unknown for most infant botulism cases.”1

It was Dr. Arnon who led the discovery that honey can contain spores of C. botulinum, and that exposure to honey is a risk factor for some cases of infant botulism. His efforts to alert the public to avoid feeding honey to infants were joined internationally by pediatric and public health authorities, eventually resulting in voluntary labeling of commercial honey in the U.S.5 Today, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that honey should not be given to infants younger than 12 months of age. However, AAP says honey is safe for children 1 year and older.4

There is no vaccine available to prevent botulism.4

Symptoms of Infant Botulism

Symptoms are progressive, with an incubation period ranging from three to 30 days after exposure to the bacteria. Symptoms may range from mild to severe, usually appearing around 3 to 4 months of age. Typically, symptoms begin with constipation, a weakened cry, loss of facial expression, a reduced gag reflex, slow feeding and overall weakness or floppiness. Children may also have blurred or double vision, a dry mouth, drooping eyelids (ptosis), difficulty swallowing and speaking, poor feeding, sluggish pupils and a flattened facial expression. The toxin can also cause paralysis of the trunk, arms, legs and respiratory system and may possibly cause respiratory arrest.4,6

In 2020, researchers published an article in the Hawaii Journal of Health and Social Welfare that discussed two cases of infant botulism with atypical initial presentations that were diagnosed on Oahu. “Patient A is a 3-month-old male who presented with altered mental status, including inconsolability, who progressed to loss of gag reflex and constipation. Due to early concern for meningitis, Patient A was treated with antibiotics, however further evaluation led to eventual positive testing for botulinum B toxin. Patient B is a 2-month-old female who presented with somnolence and fever after immunizations and progressed to respiratory failure and apparent dehydration. Because she presented shortly after receiving immunizations, metabolic disorders were strongly considered as a potential cause of symptoms, but Patient B had normal metabolic evaluation and eventually tested positive for botulinum A toxin.” The researchers noted that altered mental status and fever are unusual presentations for infant botulism; however, they recommended infant botulism be considered in infants with altered mental status when the course of illness includes the development of constipation and weakness, and evaluations are not suggestive of alternative causes, including infection, metabolic diseases and spinal muscular atrophy.7

Diagnosing Infant Botulism

Because infant botulism has a broad spectrum of clinical severity, it may be difficult to recognize in its early stage. And, since infants are unable to describe their symptoms, the onset of infant botulism can be detected only by careful observation (see Physical Examination Signs Helpful in the Diagnosis of Infant Botulism). Nevertheless, early diagnosis is essential for prompt intervention and optimal management.8

A stool culture and direct toxin assay are needed to diagnose infant botulism. A stool culture can be obtained with an enema, but not glycerin suppositories, and a toxin assay can be obtained from stool, serum or gastric contents. Results for the direct toxin specimen are often available the morning after the specimen has been received, while the stool culture results can vary from one week to one month. It should be noted that only 60 percent of stool cultures yield a positive result. According to the authors of the continuing education activity mentioned previously, the best test is the mouse inoculation test performed by CDC. And, today, while polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is available to detect spores and the results are available within 24 to 72 hours, PCR is not readily available in all hospitals.2

No imaging is required to make the diagnosis. However, it is recommended that a lumbar puncture be performed to rule out meningitis.2

Treating Infant Botulism

BabyBIG is the only known treatment for infant botulism. According to the Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program (IBTPP) created by Dr. Arnon and colleagues, the decision to treat with BabyBIG should be based on clinical presentation and findings and should not be delayed by waiting for results of laboratory confirmatory testing.9

BabyBIG (first known as BIG-IV) was developed by Dr. Arnon following the passage of the federal Orphan Drug Act of 1983. Dr. Arnon received funding from the FDA Office of Orphan Products Development to conduct a clinical trial of BIG-IV in California from 1992 through 1997. This was followed by a six-year nationwide open-label study of BIG-IV from 1997 to 2003, culminating in FDA licensure of BIG-IV as BabyBIG on Oct. 23, 2003.5 BabyBIG is the standard of care for infant botulism and shortens hospital stay by an average of three-and-a-half weeks. It is an expensive treatment, costing close to $50,000; however, it results in a decrease in hospital stays and, thus, charges.2

According to a study published in 2017, since its licensure in 2003, BabyBIG has treated approximately 93 percent of U.S. patients with laboratoryconfirmed infant botulism. In the study, medical records and billing information were collected for U.S. patients treated with BabyBIG from 2003 to 2015. Length of hospital stay (LOS) and hospital charge information for treated patients were compared with the BIGIV Pivotal Clinical Trial Placebo Group to quantify decreases in LOS and hospital charges, with results showing the use of BabyBIG reduced mean LOS from 5.7 to 2.2 weeks, with a mean decrease in hospital charges of $88,900 per patient. For all U.S. patients from 2003 to 2015, total decreases in LOS and hospital charges were 66.9 years and $86.2 million, respectively.10

Approximately 50 percent of infantile botulism cases will require intubation and an advanced airway even if they have been treated with BabyBIG; however, those who are not treated may require mechanical ventilation longer. In addition, it is recommended that after resolution, all live-virus vaccinations should be delayed by five months.2

Most children recover fully from botulism, although it can take several weeks to months.4

IBTPP’s Success for Infant Botulism

In 1992, Dr. Arnon established IBTPP, a unit of the California Department of Public Health, which is a public service program that provides clinical consultation and access to the treatment BabyBIG for infants suspected of having infant botulism. The organization aims to improve the treatment of infant botulism and prevent the disease by offering 24/7 consultation to healthcare providers regarding diagnosis and management of suspected cases, particularly focusing on early intervention with BabyBIG.11

Compared to a century ago when the mortality rate was close to 90 percent for this rare but serious disease, today the mortality rate is less than 15 percent2 due to the passage of the Orphan Drug Act and the almost 15 years of clinical research conducted by Dr. Arnon and colleagues that resulted in FDA approval of BabyBIG. As of May 31, 2024, the IBTPP website states that BabyBIG has been administered to more than 2,180 infants in 48 states and Washington, D.C., and has resulted in more than 128 years of avoided hospital stays and more than $174 million of avoided hospital costs. And, on average, infant botulism patients have an approximately 3.6 week reduction in time spent in the hospital, resulting in more than $94,000 in avoided hospital costs (when compared to the pivotal clinical trial placebo group).9,11

References

- Harris, RA, and Dabritz, HA. Infant Botulism: In Search of Clostridium botulinum Spores. Current Microbiology, 2024 Aug;81(306). Accessed at link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00284-024-03828-0.

- Van Horn, NL, and Street, M. Infantile Botulism. StatPearls, last update June 12, 2023. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493178.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Botulism Surveillance Summary, 2019, updated May 13, 2024. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/botulism/php/national-botulism-surveillance/2019.html.

- Healthychildren.org. Botulism. Accessed at www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/infections/Pages/Botulism.aspx.

- Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program. Rest in Peace Dr. Stephen Soulé Arnon. Accessed at www.infantbotulism.org.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Overview of Infant Botulism. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/botulism/hcp/clinical-overview/infant-botulism.html.

- August, M, and Hamele, M. Two Cases of Infant Botulism Presenting with Altered Mental Status. Hawaii Journal of Health and Social Welfare, 2020 May 1;79(5 Suppl 1):101–103. Accessed at pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7260868.

- Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program. Clinical Diagnosis. Accessed at www.infantbotulism.org/physician/clinical.php.

- California Department of Public Health. Infant Botulism Treatment and Prevention Program: How to Obtain Clinical Consultation and Order BabyBIG. Accessed at www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/ObtainBabyBig.aspx.

- Payne M, JR, Khouri, JM, Jewell, NP, and Arnon, SS. Efficacy of Human Botulism Immune Globulin for the Treatment of Infant Botulism: The First 12 Years Post Licensure. The Journal of Pediatrics, 2018 Feb;193:172-177. Accessed at www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022347617314397.

- Arnon, SS. Creation and Development of the Public Service Orphan Drug Human Botulism Immune Globulin. Accessed at www.infantbotulism.org/readings/Peds_Creatn_Devlpmt_BIG_IV_apr07.pdf.