Advances in Treating Menopause

Menopause is a normal, natural event in every woman’s life, but it can cause a variety of uncomfortable symptoms. New therapies show promise for bringing relief and an improved quality of life.

- By Jim Trageser

PEOPLE HAVE had theories about menopause long before we possessed the medical knowledge to actually understand it. With cultures across the ancient world all fascinated by fertility (as well they might, given their shorter average lifespans and the need to have children to carry a community into the future), the late-in-life loss of fertility that visited any woman who lived long enough was equally a source of fascination.

In fact, menstruation and menopause were observed with a mix of both suspicion and curiosity. Ancient Judaism viewed menstruation as unclean. In the fourth century B.C., Aristotle wrote about the idea of menopause, citing that women experienced it at an average age of 50. During the Roman empire, Pliny the Elder ascribed the power to dull blades and kill crops to menstrual blood. Much later in 1821, French physician Charles-Pierre-Louis de Gardanne came up with the term “menopause” from a combination of the Greek words for “monthly” and “cessation.” From that point on, our attempts to understand the biological changes associated with menopause became steadily more scientific and less superstitious.1

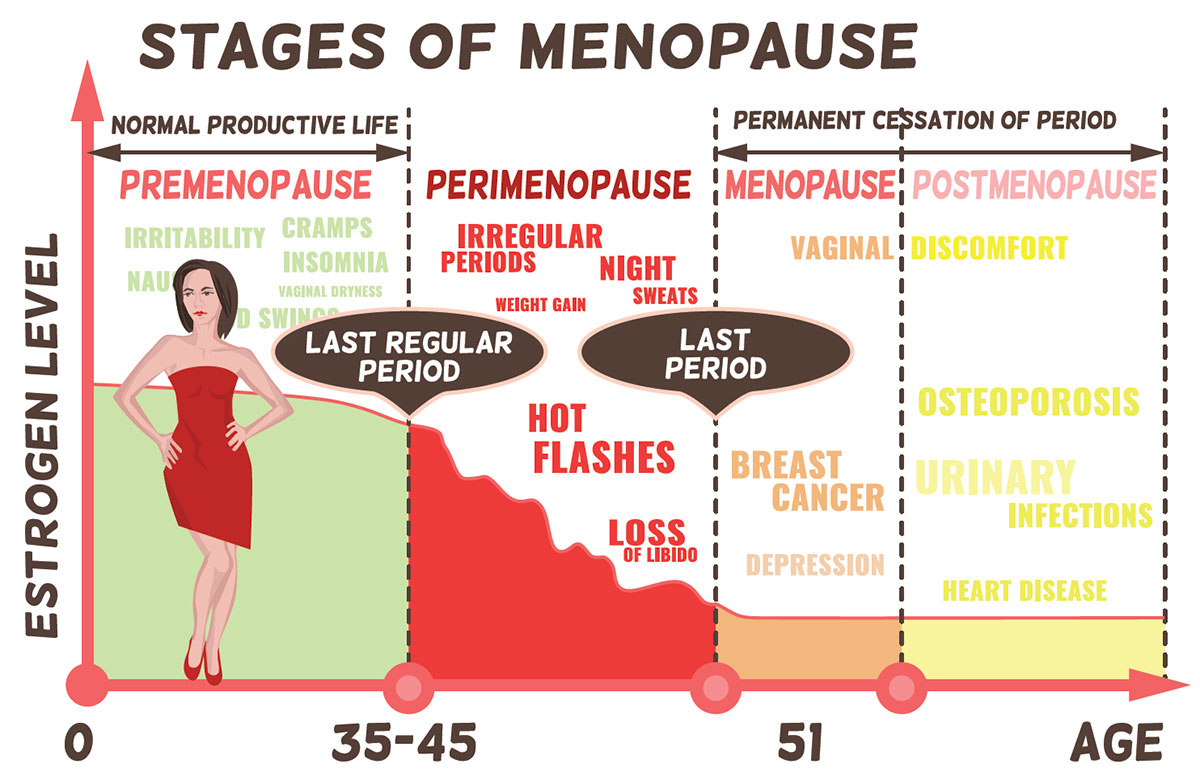

In today’s popular culture, menopause is understood to refer to the entire stretch of a woman’s life as she both approaches menopause and then moves past it, but menopause is actually the moment that marks the time in a woman’s life when her body no longer has the ability to conceive a child. While some symptoms of this transitional time are merely uncomfortable, other conditions that emerge postmenopause such as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease can pose significant health and even mortality risks to women. Fortunately, researchers continue to make new advances in both understanding the processes behind menopause and in developing new therapies to ameliorate both the discomfort and risks associated with it.

What Is Menopause?

The National Institutes of Health defines menopause as the moment a woman has gone 12 months without having a menstrual period.2 Colloquially, the word “menopause” is generally understood as the stretch of a woman’s life as she both approaches that moment and then moves past it, but the technical terms for these stages are “perimenopause” and “postmenopause.”

Perimenopause is the time during which a woman’s body naturally transitions to menopause, which marks the end of her reproductive years. This is also known as the menopausal transition.3

Postmenopause is the time after a woman’s body has been without a menstrual period for 12 months.4

Technically, a woman transitions straight from perimenopause to postmenopause without ever actually being “in menopause.”

Causes and Symptoms of Menopause

As a woman ages, the reproductive period of her life comes to a normal, natural end. Perimenopause typically begins in a woman’s mid-40s and can last between two to eight years (on average, it lasts for four years); the average age of menopause is 51 years.5 During perimenopause, the amount of hormones produced by a woman’s ovaries begins to decrease, and as a result, her periods become less regular, both in terms of timing and amount of menstrual blood passed. Ovulation becomes less regular as well. (However, pregnancy is still possible as long as she is still having periods.) A woman’s body may experience unpleasant symptoms such as hot flashes; night sweats; vaginal dryness and painful sexual intercourse; mood swings, depression or irritability; insomnia; weight gain; and urinary incontinence.6 Women who have their ovaries surgically removed will experience immediate menopause after surgery, and will effectively enter the postmenopausal phase of life. They will then be subject to postmenopausal symptoms, which often include weakening of bone density and an increase in blood pressure.5

Menopause cannot be prevented or “cured,” but there are treatments available to help ease the discomfort of symptoms associated with perimenopause and postmenopause. Symptoms of perimenopause are not life-threatening or dangerous, but instead affect women’s quality of life. Postmenopausal women may continue to experience some of the same symptoms common during perimenopause, and their risk of some medical conditions increases, most notably osteoporosis and/or cardiovascular disease, which may quietly begin (postmenopausal women are at a higher risk of these conditions). Therefore, working with women to identify and address their symptoms is important not only for quality of life, but the length of life as well.

Perimenopausal Therapies

Medical intervention is not required for perimenopausal women unless symptoms are interfering with their quality of life. When that happens, patients have several options to discuss with their healthcare provider:

• Hormone replacement therapy (HRT). HRT replaces the natural hormones a woman’s body no longer makes. There are two types of HRT: estrogen therapy and combination therapy. Estrogen therapy involves taking estrogen only; combination therapy involves taking a combination of estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen therapy may be administered through an oral pill, patch, topical gel, topical spray, vaginal ring, vaginal cream or vaginal tablets. Combination therapy may be administered through an oral pill, topical patch or an intrauterine device. Estrogen therapy should be used at the lowest dose needed to alleviate symptoms. Combination therapy is best for women who have not had a hysterectomy, as estrogen and progesterone are important for uterine health.

HRT is the most common therapy prescribed to ease the many uncomfortable symptoms of perimenopause. However, HRT does carry some risks, including an increased risk of uterine cancer, breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, gallbladder disease, blood clots and stroke. Risks of complications from HRT are lower when HRT is started before age 60 or within 10 years of menopause. Taking HRT when a woman is in her 40s and 50s is not typically associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.6,7,8 Recommendations for HRT are based on women’s symptoms and medical history, their family history and their overall health.9

• Bioidentical hormone replacement therapy (BHRT). A growing number of patients have been exploring BHRT as a natural alternative to traditional HRT. HRT uses synthetic hormones with a chemical structure similar to human hormones; BHRT uses hormones that come from plants, usually from wild yams, cactus or soy. The structure and function of these hormones is identical to human hormones. The hormones are extracted in a lab and then sent either to compounding pharmacies where individualized dosages are made according to patient need, or to pharmaceutical companies where proprietary formulas and products such as pills, patches, gels and creams are developed under strict U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations.10

FDA has approved many BHRT products that have been reviewed for safety and efficacy and are indicated for treating symptoms resulting from hormonal changes associated with menopause.11 Examples of these products include Bijuva capsules and Imvexxy vaginal inserts. FDA-approved BHRT carries the same risks as HRT (increased risk for certain cancers, cardiovascular disease, blood clots, stroke, gallbladder disease). Compounded BHRTs are not produced under FDA’s strict regulations, so they have not been evaluated for safety or effectiveness. However, compounding pharmacies must adhere to state pharmacy board regulations. In some patients, compounded BHRT may be a better choice because dosage can be customized according to individual patients’ needs.10,12,13 (See “Innovations in Bioidentical Hormone Replacement Therapy” on p.36.)

• Antidepressants. While less efficacious than hormone replacement, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may reduce discomfort from hot flashes in some women. Various SSRIs have been used off-label with varying levels of effectiveness, but FDA has approved the low-dosage form of the antidepressant paroxetine (Brisdelle) specifically for treating hot flashes. This option is helpful for women who cannot use hormone therapies for health reasons.14

• Fezolinetant (Veozah). Approved by FDA in May 2023, Fezolinetant (Veozah) is the first nonhormonal drug designed specifically to treat hot flashes and night sweats. It works by addressing the brain’s regulation of body temperature. It does carry the risk of liver damage, so ongoing blood testing is a requirement (similar to the use of statins in treating cholesterol).15

• Professional counseling and lifestyle changes. Mood changes are a major concern during perimenopause. In fact, about four in 10 women have mood changes during perimenopause that leave them feeling irritable, tearful or low on energy; some also experience difficulty concentrating. Studies show the risk of depression increases during this transitional time, too. Antidepressants and antianxiety drugs may be considered when symptoms are more pronounced and interfering with daily life, but sometimes mood changes can be addressed through professional therapy or lifestyle changes. Maintaining a healthy diet, exercising regularly, getting regular sleep and cutting back on caffeine can also help reduce the intensity of these symptoms.16

Postmenopausal Risks and Therapies

After menopause, women’s risk of developing osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease increases because their bodies are making smaller amounts of estrogen, which is a critical component of building and maintaining healthy bones and guarding against heart attacks, cardiovascular disease and stroke.4 Both osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease can be silent and go unnoticed by patients because they cause no immediate distress or discomfort. However, falls remain a major cause of mortality among the elderly, and osteoporosis disproportionately increases the danger of a fall.17,18,19 Testing for both osteoporosis and cardiovascular conditions should be conducted as part of regular postmenopausal women’s healthcare.

Some therapies may help mitigate against these conditions. Options include:

• HRT. Using estrogen for preventing and slowing osteoporosis is the frontline treatment in many parts of the world. It was first approved for use in the United States during World War II. While the side effects led European authorities to recommend against HRT more than two decades ago, some researchers believe that decision was in error and its benefits continue to outweigh its risks. HRT may also offer benefits in treating postmenopausal cardiovascular disease. (A recent study says HRT does not improve long-term outcomes, so more study is clearly needed to give physicians clear guidance.) However, drugs that lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels can also be considered to treat women with postmenopausal cardiovascular disease.4

• Bisphosphonates. While HRT may be helpful, the most widely prescribed treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis is a family of drugs known as bisphosphonates, which have been in use since the 1990s. Bisphosphonates slow bone loss by inhibiting the activity of osteoclast cells, which break down old bone to make room for new bone. As new bone generation slows during postmenopause, bisphosphonates can help balance the process to preserve bone density and thus strength. Some commonly used bisphosphonates include alendronate (Fosamax), ibandronate (Boniva) and risedronate (Actonel), all of which can be taken orally. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronic acid (Reclast, Zometa) are given via intravenous (IV) administration, and ibandronate can also be given both intravenously and orally. Mild side effects of oral bisphosphonates are esophageal and stomach reactions, while mild side effects of IV bisphosphonates include flu-like symptoms such as fever and achiness.20,21

• Denosumab (Prolia, Jubbonti). Denosumab gained FDA approval in 2010. It may be a better fit for women who suffer significant side effects from or otherwise need to avoid bisphosphonates (those with kidney disease, for instance). Denosumab is administered via subcutaneous injection and works by blocking a protein the osteoclast cells require. However, denosumab can result in dangerously low calcium levels in the blood; calcium levels must be tested during the course of the treatment.22

• Human parathyroid hormone (teriparatide, abaloparatide). For women at high risk of a fracture, doctors may prescribe a bone anabolic drug that promotes new bone growth. Currently, two synthetic forms of the human parathyroid hormone (teriparatide and abaloparatide) are available. However, because of side effects and a waning effectiveness over time, these can be used only on a limited basis.23,24

• Romosozumab-aqqg (Evenity). Approved just five years ago, an even newer treatment for osteoporosis is the combination anabolic plus antiresorptive drug romosozumab (Evenity). However, there may be significant cardiovascular side effects with romosozumab, and the drug loses its effectiveness at promoting new bone growth after 12 monthly injections, so it is not a long-term treatment.24,25

Looking Ahead

As a very natural part of human life, menopause will be with us for the foreseeable future. But new therapies for managing uncomfortable side effects of perimenopause and mitigating more serious conditions that may occur during postmenopause offer physicians new tools for helping women elevate the quality and extend the length of their lives.

References

1. Baron, Y. A History of the Menopause. University of Malta Press, 2012. Accessed at www.researchgate.net/publication/304346490_A_History_of_the_Menopause.

2. National Institute on Aging. What Is Menopause? Accessed at www.nia.nih.gov/health/menopause/what-menopause.

3. Mayo Clinic. Perimenopause. Accessed at www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/perimenopause/symptoms-causes/syc-20354666.

4. Cleveland Clinic. Postmenopause. Accessed at my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21837-postmenopause.

5. Mayo Clinic. Menopause. Accessed at www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/menopause/symptoms-causes/syc-20353397.

6. Cleveland Clinic. Hormone Therapy for Menopause Symptoms. Accessed at my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/15245-hormone-therapy-for-menopause-symptoms.

7. Hodis, H, and Mack, W. Menopausal Hormone Replacement Therapy and Reduction of All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease: It’s About Time and Timing. The Cancer Journal, May-Jun 01;28(3):208-223. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9178928.

8. Manson, J, Crandall, C, Rossouw, J, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trials and Clinical Practice. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2024;331(20):1748-1760. Accessed at jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2818206.

9. Mayo Clinic. Menopause Diagnosis and Treatment. Accessed at mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/menopause/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353401.

10.Woods, J. Clarifying the Terms “Bioidentical Hormones” and “Compounded Hormones.” Obstetrics and Gynecology: menoPAUSE Blog, April 23, 2015. Accessed at www.urmc.rochester.edu/ob-gyn/ur-medicine-menopause-and-womens-health/menopause-blog/april-2015/clarifying-terms-bioidentical-hormones-compounded.aspx.

11. Jackson, LM, Parker, RM, and Mattison, DR. The Clinical Utility of Compounded Bioidentical Hormone Therapy: A Review of Safety, Effectiveness and Use. National Academies Press (US), July 1, 2020. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562877.

12. Billingsley, A. Bioidentical Hormone Replacement Therapy for Menopause: Safety, Uses and Cost. GoodRX, May 27, 2022. Accessed at goodrx.com/conditions/menopause/bioidentical-hormone-therapy.

13. Cleveland Clinic. Bioidentical Hormones. Accessed at my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/15660-bioidentical-hormones.

14. Mayo Clinic. Hot Flashes. Accessed at www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hot-flashes/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20352795.

15. Godman, H. FDA Approves First Drug Designed to Treat Hot Flashes. Harvard Health, Aug. 1, 2023. Accessed at www.health.harvard.edu/womens-health/fda-approves-first-drug-designed-to-treat-hot-flashes.

16. Silver, N. Mood Changes During Perimenopause Are Real. Here’s What to Know. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, April 2023. Accessed at www.acog.org/womens-health/experts-and-stories/the-latest/mood-changes-during-perimenopause-are-real-heres-what-to-know.

17. Meyer, F, König, HH, and Hajek, A. Osteoporosis, Fear of Falling, and Restrictions in Daily Living. Evidence From a Nationally Representative Sample of Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Frontiers in Endocrinology, Sept. 26, 2019. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6775197.

18. Stevenson, J. Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis in Women. Post Reproductive Health, Nov. 10, 2022. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10009319.

19. Cleveland Clinic. Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts. Accessed at my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24871-osteoblasts-and-osteoclasts.

20. Cleveland Clinic. Bisphosphonates. Accessed at my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/24753-bisphosphonates.

21. Ganesan, K, Goyal, A, and Roane, D. Bisphosphonate. StatPearls, July 2, 2023. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470248.

22. MedlinePlus. Denosumab Injection. Accessed at medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a610023.html.

23. Mayo Clinic. Teriparatide (Subcutaneous Route). Accessed at www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/teriparatide-subcutaneous-route/description/drg-20066280.

24. Adami, G, Fassio, A, Gatti, D, et al. Osteoporosis in 10 Years Time: A Glimpse into the Future of Osteoporosis. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease, March 20, 2022. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8941690.

25. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Treatment for Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women at High Risk of Fracture, April 9, 2019. Accessed at www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-treatment-osteoporosis-postmenopausal-women-high-risk-fracture.