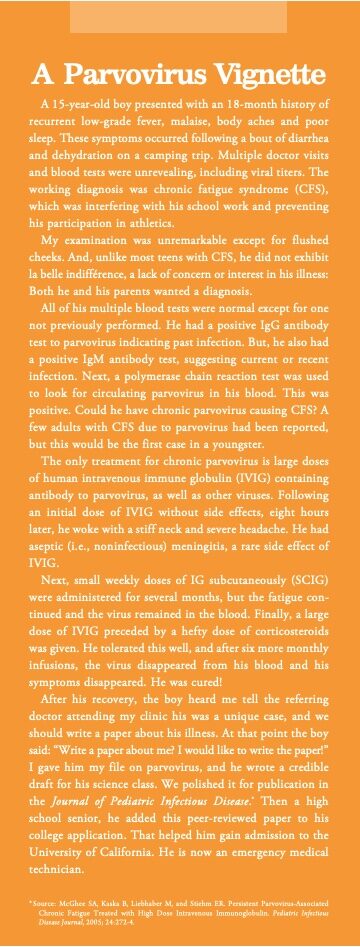

The Many Faces of Parvovirus B19: IVIG to the Rescue?

This common virus manifests in a host of systemic illnesses that are mostly curable with human intravenous immune globulin therapy.

- By E. Richard Stiehm, MD

PARVOVIRUS B19 INFECTION is a common viral infection that most individuals will contract in their lifetime. Usually, it is acute, but sometimes it is chronic. The infection can cause a wide spectrum of clinical disorders, both acute and chronic, the latter of which are mostly curable with human intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) therapy.

The presence of IgG antibodies to the virus indicates past infection. These antibodies, which are present in 70 percent to 80 percent of older adults and 25 percent to 35 percent of young adults, provide lifetime immunity to parvovirus and explain their presence in the plasma pools used for IG manufacture.

Parvovirus was first identified in 1975 in plate B of serum 19 during a search of blood specimens for the hepatitis B virus,1 thus the term parvovirus B19. It is a DNA virus that like other DNA viruses does not mutate.2,3 Other strains of parvovirus occur in animals, but only B19 afflicts humans. Its receptor is the red blood cell P antigen present in most people, except for those with the rare blood type PP who cannot be infected.4 The P receptor is strongly expressed on erythroid precursors, but also on megakaryocytes, hepatocytes, endothelial cells and fetal myocardium, which explains the rarer forms of parvovirus infection.5

Diagnosis of parvovirus B19 is suspected by identifying serum parvovirus IgM antibodies with or without IgG antibodies and confirmed by PCR for circulating virus.2,3

Individuals can be infected with parvovirus B19 year-round, but childhood epidemics may occur in late winter and early spring. 2 Infection is usually spread by close contact with an infected subject. Less commonly, it is acquired by blood products or from stem cell or organ transplant from an infected donor.2,6-8

Manifestations of Parvovirus B19

Slapped cheek syndrome. Acute slapped cheek syndrome (i.e., erythema infectiosum, fifth disease) is the most common manifestation of parvovirus infection (Figure). After an incubation period of seven days to 14 days, the child develops a three- to 10-day episode of fever, chills and malaise followed by a fiery red rash of the cheeks.2 This may be followed by a generalized macular rash and mild arthritic symptoms. When the rash appears, the child is no longer contagious.

Acute and chronic aregenerative anemias. When parvovirus B19 attaches to erythroid precursors via the P antigen, the result is cellular death and interruption of erythropoiesis. This then results in a progressive normocytic, normochromic anemia with absence of reticulocytes. The anemia can be acute or chronic, often occurring in patients with another chronic health problem.

Pure red cell aplasia is the most severe form of parvovirus anemia leading to sudden cessation of erythropoiesis with pallor fatigue and weakness that often requires red blood cell transfusions. 9 In many cases, the disorder is self-limiting if the patient makes a neutralizing antibody. However, this may not occur if the patient has an underlying immune deficiency.

Chronic aregenerative anemias are common in patients with increased erythropoietic activity due to a hemolytic anemia (e.g., hydrops fetalis) or a hemoglobinopathy (e.g., sickle cell anemia).10-12 Parvovirus-induced anemia may also occur in primary or secondary immunodeficiency (e.g., HIV infection), during immunosuppressive treatment for hematologic malignancies or following organ transplantation.13-15

Parvovirus during pregnancy/hydrops fetalis. About 4 percent of seronegative women develop parvovirus during pregnancy.12,13 Of special risk are school teachers, day care workers or mothers of school-age children. Fetal loss occurs in 5 percent of these infections, nearly always from infection in the first half of pregnancy.

About 10 percent of pregnant women with a parvovirus infection transmit the virus to their fetus. The fetus may develop hydrops fetalis with severe anemia, ascites, heart failure and possible death (10 percent).10,16 Affected fetuses can be treated with an intrauterine blood transfusion.17 One hydropic fetus was successfully treated with intraperitoneal IG.18 Some surviving infants are born with anemia, myocarditis, hepatitis or central nervous system problems. Yet, despite these illnesses, parvovirus is not considered a teratogen.

Other illnesses. Parvovirus may cause an acute transient arthritis resembling Lyme disease or rheumatoid arthritis. It is particularly common in young females, usually affecting the wrists and fingers.19

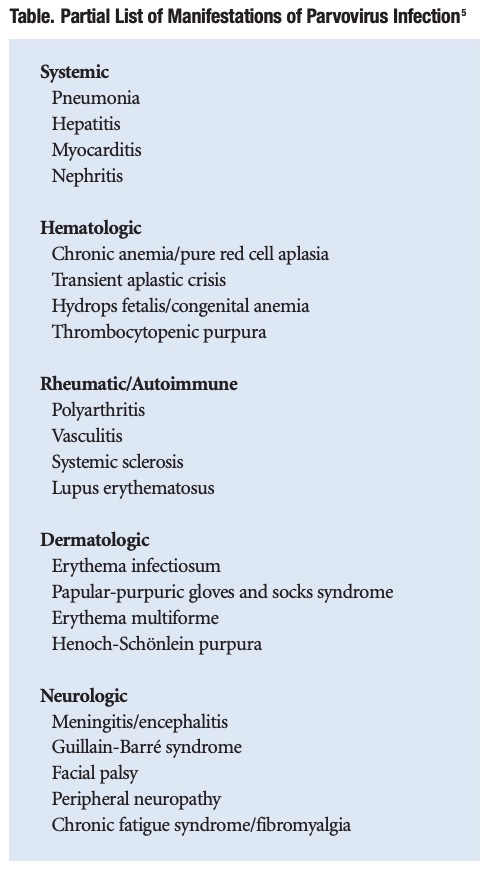

More than 50 other systemic illnesses have been caused by parvovirus (Table). These include systemic, hematologic, rheumatic/autoimmune, dermatologic and neuro/psychiatric disorders. Therefore, parvovirus should be suspected in any undiagnosed chronic illness, particularly if the patient had a sudden onset of disease or a possible exposure to an infected subject.

Prevention and Treatment

No vaccine or antiviral drugs for parvovirus are available. Hospitalized patients with parvovirus anemias should be kept in isolation. Pregnant women exposed to a child with erythema infectiosum can be tested for immunity to the virus. A pregnant woman with parvovirus should be monitored by ultrasonography for carrying a hydropic infant.20 Organ and stem cell donors can be tested for parvovirus prior to transplant. Blood donors are not routinely tested for parvovirus.8

Since IVIG has high titers of parvovirus antibody, chronic parvovirus infections can be treated with 400 mg/kg to 600 mg/kg per week of IVIG for one month.9,14,15,21 This is my recommendation, although there is no standardized dose or duration of IVIG therapy. Other patients may require long-term IVIG therapy such as in the vignette or those with compromised immune systems. The effectiveness is determined by clearance of the virus from the blood three months after completing IVIG therapy.

References

- Cossart YE, Field AM, Cant B, et al. Parvovirus-Like Particles in Human Sera. Lancet, 1975: 1;72-73.

- RogoL, Mokhtari-Azad T, Kabir MH, et al. E Human Parvovirus B19: A Review. Acta Virologica, 2014; 58;199-213.

- Landry ML. Parvovirus B19. Microbiol Spectrum, 2015; 4;1-10.

- Brown KE, Hibbs JR, Gallinella G, et al. Resistance to Parvovirus B19 Infection Due to Lack of Virus Receptor (Erythrocyte P Antigen). New England Journal of Medicine, 1994 ;330: 1192

- Schulte D. Parvovirus B19, in Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, edition 8; Edited by Cherry JC, et al. Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2018, pp 1332-1341.

- Yu MY,Alter HJ, Virata-Theimer ML, et al. Parvovirus B19 Infection Transmitted by Transfusion of Red Blood Cells Confirmed by Molecular Analysis. Transfusion, 2010; 50: 1712-21.

- Yango A Jr, Morrissey P, Gohh R, et al. Donor-Transmitted Parvovirus Infection in a Kidney Transplant Recipient Presenting as Pancytopenia and Allograft Dysfunction. Transplant Infectious Disease, 2002: 4: 1631-66

- Juhl D and Hennig H. Parvovirus B19: What Is the Relevance in Transfusion Medicine? Frontiers in Medicine, 2018; 5:1-10.

- Kurtzman G, Frickhofen N, Kimball J, et al. Pure Red-Cell Aplasia of 10 Years’ Duration Due to Persistent ParvovirusB19 and Its Cure with Immunoglobulin Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine, 1989; 321:519-523.

- Ornoy A and Ergaz Z. Parvovirus B19 InfectionDuring Pregnancy and Risks to the Fetus. Birth Defects Research, 2017, 109: 311-323.

- Hankins JS, Penkert, RR, Lavole P, et al. Parvovirus B19 Infection in Children with Sickle Cell Disease in the Hydroxyurea Era. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 2016; 241: 749-754.

- Goldstein AR, Anderson MJ, and Serjeant GR. Parvovirus Associated Aplastic Crisis in Homozygous Sickle Cell Disease. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1987; 62: 585.

- Koduri PR. Parvovirus B19-Related Anemiain HIV-Infected Patients. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 2000 14:7.

- Katragadda L, Shahid Z and Restrepo A. Preemptive Intravenous Immunoglobulin Allows Safe and Timely Administration of Antineoplastic Therapies in Patients with Multiple Myeloma and Parvovirus B19 Disease. Transplant Infectious Disease, 2013; 15:354-360.

- Isobe Y, SugimotoK, Shiraki Y, et al. Successful High-Titer Immunoglobulin Therapy for Persistent Parvovirus B19 Infection in a Lymphoma Patient Treated with Rituximab-Combined Chemotherapy. American Journal of Hematology, 2004; 77:370.

- Bonvicini F, Bua G, and Gallinella G. Parvovirus B19 in Pregnancy — Awareness and Opportunities. Current Opinion in Virology, 2017 27. 8-14.

- Lindenburg ITM, van Kamp IL, and Oapkes D. Intrauterine Blood Transfusion: Current Indications and Associated Risks. Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy, 2014:36:263-271.

- Matsuda H, Sakaguchi K, Shibasaki T, et al. Intrauterine Therapy for Parvovirus B19 Infected Symptomatic Fetus Using B19 IgG-Rich High Titer Gammaglobulin. Journal of Perinatal Medicine, 2005: 33: 561-563.

- Mauermann M, Hochauf-Stange K, Kleymann A, et al. Parvovirus Infection in Early Arthritis. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 2016; 34: 207-13.

- Krause I, Wu R , Sherer Y, et al. In Vitro Antiviral and Antibacterial Activity of Commercial Intravenous Immunoglobulin Preparation — A Potential Role for Adjuvant Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy in Infectious Diseases. Transfusion Medicine, 2002, 12 133-139.

- Grabol Y, Terrier B, Rozenberg F, et al. Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy for Pure Red-Cell Aplasia Related toHuman Parvovirus B19 Infection: A Retrospective Study of 10 Patients and Review of the Literature. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2013; 56:968.