Addressing Workplace Violence in Healthcare Facilities

With a significant rise in workplace violence in the healthcare industry, measures are being taken to address and prevent it.

- By Abbie Cornett

WHEN CONSIDERING entering the healthcare profession, most people may not realize its dangers. But, in fact, working in the healthcare industry in the United States can be extremely perilous, with practitioners reporting being routinely physically or verbally assaulted by the people they are trying to help. Lisa Tenney of the Maryland Emergency Nurses Association is a prime example. “I have been bitten, kicked, punched, pushed, shoved, scratched and pushed,” said Tenney. “I have been bullied and called very ugly names. I’ve had my life, the life of my unborn child and of my other family members threatened, requiring security escort to my car.”1 The majority of assaults are committed by patients, but violent threats can come from many different sources. Family members, disgruntled employees and drug seekers all pose a potential threat to safety. As such, action is needed to both address and prevent this serious issue.

Scope of the Problem

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA), workplace violence in healthcare is four times higher than in private industry, and those numbers are growing (Figure 1). The most recently reported statistics by BLS show “intentional injury’’ by another person rose from 6.4 incidents per 10,000 hospital workers in 2016 (the most recent year of data).2

More alarmingly, research shows violence in healthcare settings is frequently either underreported or not reported at all. It is estimated less than half of all incidents are recorded.3 The reason: Reporting is voluntary, so many victims don’t report incidents. Indeed, victims often believe their assailants are not responsible for their actions since their mental state has been altered due to their condition.1

Who Is at Risk?

Workplace violence is a problem that affects everyone, from those who work with patients, to the patients, family members and visitors. While everyone is vulnerable, nurses and nursing assistants bear the brunt of assaults because they usually have the most patient contact. In addition, incidents of assault increase for professionals who work in higher risk settings such as emergency departments, inpatient mental health facilities, homecare and long-term residential care facilities.

A study conducted on emergency department violence by the Emergency Nurses Association found 55.6 percent of nurses reported they had experienced physical violence, verbal violence or both.4 And, the American College of Emergency Physicians released the results of its survey of 3,500 emergency physicians in October 2018 that called attention to the scope of violence against emergency room physicians: Nearly half (47 percent) reported having been physically assaulted while at work, with 60 percent saying those assaults occurred in the last year.2

The Root of the Problem

Why rates of violence are so high in healthcare settings is not easy to answer. Like first responders, healthcare professionals come into direct contact with a wide range of people, many of whom are under stress due to pain, illness or circumstances beyond their control.

Many incidents of violence, particularly those that occur in emergency rooms, can be traced to a number of critical unresolved social and healthcare issues, including diminishing resources for behavioral health, increasing opioid addiction, domestic violence and patients in police custody. In addition, factors that increase risk to emergency care providers include 24-hour access, unrestricted visitor access, overcrowding, long waiting periods and access to drugs.

Consequences of Violence

While violence against healthcare providers can be viewed as an occupational hazard, it can have real and devastating consequences for victims. Frequently, providers feel they are equipped to cope with violence because of their training. But, this is rarely the case. Healthcare workers suffer from many of the same physical and psychological consequences as any other victims, including physical injury, permanent disability or death, missed days of work and limited time to recover from injuries, as well as longer-term physiological and psychological consequences that include feelings of anger, fear, depression, guilt and symptoms suggestive of posttraumatic stress disorder such as increased startle response, changes in sleep patterns, increased body tension and generalized body soreness.5

While violence against healthcare providers can be viewed as an occupational hazard, it can have real and devastating consequences for victims. Frequently, providers feel they are equipped to cope with violence because of their training. But, this is rarely the case. Healthcare workers suffer from many of the same physical and psychological consequences as any other victims, including physical injury, permanent disability or death, missed days of work and limited time to recover from injuries, as well as longer-term physiological and psychological consequences that include feelings of anger, fear, depression, guilt and symptoms suggestive of posttraumatic stress disorder such as increased startle response, changes in sleep patterns, increased body tension and generalized body soreness.5

Besides the human toll of violence, there is a significant financial impact on the nation’s hospitals and long-term care centers. If an employee is injured and requires medical treatment or misses work, workers’ compensation insurance typically covers the cost. If the hospital is self-insured, it will have to bear the full cost, which can be significant. For example, one hospital system had 30 nurses who required treatment for violent injuries in a particular year, which came to a total cost of $94,156 ($78,924 for treatment and $15,232 for lost wages).6

In addition, injuries and stress can lead to fatigue and burnout that can result in people leaving the profession at a time when they are desperately needed. More importantly, caregiver burnout is a potential threat to quality of care and patient safety. It can result in poorer interactions with patients, resulting in substandard care, medical errors, poorer patient outcomes and higher rates of readmission.7

Responding to Violence

In response to the rising number of assaults, healthcare executives and providers, as well as policymakers, have taken action in myriad ways. Nine states (California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New York, New Jersey, Oregon and Washington) have enacted legislation mandating healthcare facilities implement workplace violence prevention programs.8 These laws vary considerably in substance and scope. For instance, New Jersey’s law encompasses the healthcare sector, but Maine’s includes only hospitals.3 California’s legislation requires healthcare employers to identify specific risk factors for each unit throughout a facility, and to establish procedures to correct any workplace violence hazards, including providing adequate staffing to protect nurses, other workers, patients, families and visitors. In fact, California’s regulations are so stringent that Cal/OSHA is considering expanding its workplace violence regulations, which affect only healthcare facilities, to cover employers in all industries.9

In response to the rising number of assaults, healthcare executives and providers, as well as policymakers, have taken action in myriad ways. Nine states (California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New York, New Jersey, Oregon and Washington) have enacted legislation mandating healthcare facilities implement workplace violence prevention programs.8 These laws vary considerably in substance and scope. For instance, New Jersey’s law encompasses the healthcare sector, but Maine’s includes only hospitals.3 California’s legislation requires healthcare employers to identify specific risk factors for each unit throughout a facility, and to establish procedures to correct any workplace violence hazards, including providing adequate staffing to protect nurses, other workers, patients, families and visitors. In fact, California’s regulations are so stringent that Cal/OSHA is considering expanding its workplace violence regulations, which affect only healthcare facilities, to cover employers in all industries.9

At the federal level, Congressman Joe Courtney (D-Conn.) introduced H.R. 7141, the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Services Workers Act. The bill compels OSHA to complete “stalled” healthcare workplace violence safety standards, and seeks to “create an enforceable standard to ensure that employers are taking these risks seriously, and creating safe workplaces that their employees deserve.”10 Key elements of the bill include requiring a safety plan so there is a clear protocol in place when patients become violent, requiring follow-up and investigation of any incidents of violence, and protecting employees who call 911 against any professional punishment or retaliation.

Preventive Violence Measures

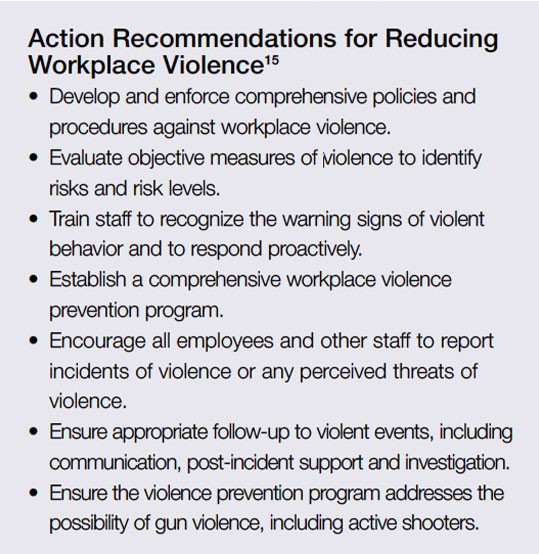

Many instances of workplace violence can be minimized or eliminated by implementing violence prevention programs that teach workers to perform a hazard evaluation and conduct proper training for staff. Following are six critical steps to help prevent workplace violence:11

1) Adopting a zero-tolerance policy toward workplace violence that covers all workers, patients, clients, visitors, contractors and anyone else who may come in contact with workers of the facility;12

2) Conducting a threat assessment to areas of risk such as parking garages or places where staff can be isolated or trapped;

3) Educating and training staff to identify people who are exhibiting behaviors that may incite the potential for violence (training should also include how staff members should respond to threats and active shooter situations, bomb threats and hostage scenarios);

4) Adopting mandatory reporting of all incidents and ensuring employees suffer no punitive actions as a result of reporting an incident;

5) Not using obscure language such as code words like code blue or code red to identify emergency situations so everyone is able to understand the situation; and

6) Establishing working relationships with local law enforcement. A good resource for information on how to evaluate and prepare a facility can be found at www.osha.gov/SLTC/workplaceviolence.

A High-Priority Issue

Until recently, not much attention has been focused on the safety of healthcare professionals. While many in the field feel the threat of violence is part of the job, it is not. Injuries inflicted by patients or family members not only pose a threat to workers, but they result in significant costs for facilities and decreased quality of care for patients. Prevention of injuries from violence and verbal assaults should be given the highest priority to ensure caregivers are physically and mentally able to provide patients with the highest level of care.

References

- Physical and Verbal Violence Against Health Care Workers. Sentinel Event Alert, Issue 59, April 17, 2018. Accessed at www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_59_Workplace_violence_4_13_18_FINAL.pdf.

- Hospital Safety Center. Violence Against Healthcare Workers Is on the Rise, Dec. 1, 2018. Accessed at www.hospitalsafetycenter.com/content/332013/topic/ws_hsc_hsc.html.

- Whitman E. Quelling a Storm of Violence in Healthcare Settings. Modern Healthcare, March 11, 2017. Accessed at www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20170311/MAGAZINE/303119990.

- Thompson P. Addressing Violence in the Health Care Workplace. Hospitals and Health Networks, July 2, 2015. Accessed at www.hhnmag.com/articles/3365-addressing-violence-in-the-health-care-workplace.

- Anderson A and West SG. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience Violence Against Mental Health Professionals: When the Treater Becomes the Victim. Innovation in Clinical Neuroscience, 2011 Mar; 8(3): 34–39. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3074201.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workplace Violence in Healthcare. Accessed at www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3826.pdf.

- Lyndon A. Burnout Among Health Professionals and Its Effects on Patient Safety. Patient Safety Network, February 2016. Accessed at psnet.ahrq.gov/perspectives/perspective/190/burnout-among-health-professionals-and-its-effect-on-patient.

- Workplace Violence Prevention in Healthcare and Social Service: Calling OSHA to Action. The National Law Review, Nov. 29, 2018. Accessed at www.natlawreview.com/article/workplace-violence-prevention-healthcareand-social-service-calling-osha-to-action.

- Castillo B. On April 1, California Healthcare Employers with No Workplace Violence Prevention Plan Will Be Breaking the Law. National Nurses United, April 2, 2018. Accessed at www.nationalnursesunited.org/blog/april-1-california-healthcare-employers-no-workplace-violence-prevention-plan-will-be-breaking.

- Bill to Address Health Care Workplace Violence Introduced in Congress. Industrial Safety & Hygiene News, Nov. 26, 2018. Accessed at www.ishn.com/articles/109819-bill-to-address-health-care-workplace-violenceintroduced-in-congress.

- Reynolds D. 6 Critical Steps to Reduce Violence in Health Care Facilities. Risk & Insurance, Nov. 15, 2018. Accessed at riskandinsurance.com/6-steps-to-reduce-violence-in-health-care-facilities.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workplace Violence. Accessed at www.osha.gov/SLTC/healthcarefacilities/violence.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Occupational Violence. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/violence/default.html.

- United States Department of Labor. DOL Workplace Violence Program — Appendices. Accessed at www.dol.gov/oasam/hrc/policies/dol-workplace-violence-program-appendices.htm.

- Violence in Healthcare Facilities. ECRI Institute, May 24, 2017. Accessed at www.ecri.org/components/HRC/Pages/SafSec3.aspx.